You are at: Home page Her Work Discography My Emigrated Bird

My Emigrated Bird

Contents

The first LP by the state-run 'Concerts Sweden Rikskonserter' produced with non-Swedish musicians. Domna Samiou was chosen for her valuable contribution to traditional Greek folk music. The LP, documented by an extended trilingual booklet, came after a concert tour in sixteen Swedish cities in the summer of 1979 aiming to inform foreign audiences on Greek culture and folk music. It was also scheduled to be distributed in Swedish schools.

Side A

-

1. Let My Eyes Go See

Peloponnese More

-

2. I’ll Be the Basil by Your Window

Epirus More

-

3. Solo floyéra

Central Greece More

-

4. The Brave Man

Crete More

-

5. My Heart-Sick Bird Flown Far From Home

Epirus More

-

6. Tsamikos

Central Greece More

-

7. Why Did I Fall in Love With You?

Macedonia More

-

8. Hassaposerviko

More

- Production: Caprice

- Year of release: 1980

- Type: LP

- Production Country: Sweden

- IBN: CAP 1191

Notes

Besides the everyday-life songs, the Greeks have a rich treasury of ballads celebrating the achievements of the Byzantine hero Dighenis Akritas, and the Klephts, well-known warriors of modern Greek history.

Dighenis Akritas was called Dighenis from his double descent, Greek and Arab, and Akritas from the fact that he fought on the Christian side on the eastern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire against the Saracens established in Syria and the East. He seems to have lived in the ninth century. In recent years an immense amount of work, notably by Professor H. Gregoire, has been done on the Akritan ballads and their relation to a more or less literary epic of the exploits of Dighenis.

The Klephts were the patriotic outlaws or bandits who kept up a continual opposition to the Turkish government in the Greek mainland, during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Klephtic ballads were first collected in 1814 by von Haxthausen and in 1824, in a much larger collection, by Claude Fauriel.

A third group of ballads, the paralogae, comprises short narratives of a swift epic character, in the form of summaries of folk traditions and folktales.

A special feature in Greek folk poetry are the distichs or rhyming couplets of which a large number have been collected. These are sometimes improvised in Crete, Cyprus and the Dodecanese in special competitions held in the form of a satirical dialogue on a given subject.

Another characteristic type of folk song, but of urban origin, is the rebétika, commonly but mistakenly known as 'bouzoukia', from the bouzouki, a long-necked kind of lute which accompanies these songs. The exchange of minorities between Greece and Turkey in 1923-4 brought over to Greece from Turkey 1 1/2 million refugees who were forced to live in very miserable surroundings mostly in Athens and Salonika. Feeling themselves on the fringes of society, the inhabitants of these slums banded together, largely through the use of drugs, and started developing a characteristically heavy type of song, dealing with such subjects as love and hashish, which had originated sometime around 1850 in prisons and places of ill-repute of such sea ports as Piraeus, Smyrna and Constantinople.

The German occupation of Greece (1941-4) spread the feeling of being outcasts in their own country to all Greeks, and this encouraged a larger acceptance of this perhaps counterpart of American urban blues. Finally a lecture on the rebétika by Hadjidakis, a noted composer, after the war, led to their acceptance by the middle class. They then led on to a period of commercialization and decline which has been broken only recently by a re-recording of some of the authentic specimens.

The predominant metrical form of Greek folk song is the fifteen syllable iambic metre, with a caesura after the eighth syllable and two main accents, one on the fourteenth, and another on the sixth or eighth syllables. It is the-metre in which much Byzantine popular, satirical and even religious verse has been written. Other common metres are the eight, ten and twelve syllable iambic and trochaic metres, and the fifteen syllable trochaic metre.

The singing of most Greek folk songs involves extension of the given line by the repetition of syllables, words or phrases, or by the interpolation of extra syllables or phrases. Several attempts have been made to explain this curious phenomenon, but none can be considered entirely satisfactory.

Another curious aspect of the relation of the words and the music in Greek folk music is that in some old songs, the cadential phrase of each strophe is built not on the final syllables of the line which is being sung, but on the opening syllables of the line which is going to follow.

In Greek folk music, as in the folk music of other countries too, it is only very rarely that two singers will be found to sing the same song in precisely the same form, for folk singers constantly introduce unexpected changes in their renderings of traditional melodies. As Cecil Sharp has pointed out 'these renderings are not corruptions, in varying degrees of one original. They are the changes, which, in the mass, engender growth and development.'

Some Greek folk tunes are more popular than others and tend to become associated with a wide variety of texts. On the other hand, we often find identical texts sung to entirely different melodies.

An attentive listener of Greek folk music will soon find out that nuptial songs, lullabies, dirges, carols, work songs and satirical songs are sung to the same or very similar melodies all over Greece. Yet there are often distinct variations in the musical style of the different areas.

The music from the Pontos region, which is now cultivated mainly in Greek Macedonia, where the Pontic Greeks settled after the exchange of minorities between Greece and Turkey in 1923-4, is characterized by a three stringed mini fiddle called the Pontic lyra or kemendjé. It is held upright on the knee and plays in parallel fourths compound metres such as 9/8 or 5/8 in a very rapid tempo.

The music of Epirus, on the NW mainland has a slow tempo and a rhapsodic character. It is based on the anhemitonic pentatonic scale and often has wide leaps in the melodic progressions, irregular metres, such as 8/8, and a profusion of glissandi. The most popular instrument of the area is the clarinet which plays in the lower register in combination with the fiddle and the lute, and sometimes the dulcimer (santouri). The clarinet was introduced in Greek folk music in the early nineteenth century, and is gradually replacing the pipiza, a double reed instrument similar to the oboe.

In the remote region of Pogoni, in North Epirus, small choral groups sing polyphonic songs in three or four parts, in which the intervals of the fourth and the second play an important part. This type of song, which is also found in Albania, is often concluded by an instrumental dance, with abrupt pauses at cadences.

The music of the remainder of the Greek mainland and the Peloponnese has a more or less unified style in which the prominent features are the 7/8, 6/4 and 2/4 metres, and the use of the seven tone scale in various diatonic, chromatic or mixed forms but never in the minor mode. The principal instruments are the same as in Epirus, but the clarinet has a tendency to play in the higher register.

In the islands the music tends to be light and delicate in character, with dance rhythms based on short, lively ostinato phrases, while in West Crete it has a heroic flavour, since the area was for many centuries the focal point of fierce struggles between Greeks, Saracens and Turks. The instruments of the islands are the fiddle, the lyra, which is gradually being replaced by the fiddle, the bagpipe, the lute and the dulcimer. The lyra is a mini fiddle like the Pontic kemendje. The clarinet has been adopted only in a few islands in the North Aegean, such as Skyros and Skopelos.

From the standpoint of melodic elaboration there are two basic styles in Greek folk music, the melismatic style with an abundance of ornaments and complete metric freedom, and the simple style with a well defined metric structure. The simple style is usually connected with dance. The melismatic style in the mainlands is usually associated with the singing of Klephtic ballads or the performance of virtuoso solos on the flute, the pípiza or the clarinet. In the islands there is no singing of Klephtic ballads, but there is a highly developed art of melismatic song which finds its finest expression in the serenades and the complaints.

Any introduction on Greek folk music is bound to land on a discussion of the folk dance, which is insolubly connected with the folk song and poetry. Of course, the discussion here will be very brief and incomplete owing to limitations of space and the vastness of the subject.

There are three basic types of Greek folk dances, the solo, the couple and the group dances. The latter are the most popular. In the group dances, a number of dancers, often men and women alternately, holding hands, or linked by holding between them the corners of handkerchiefs, form one or more open circles or lines and start moving in a counterclockwise direction.

The dancer at the right end of the circle or line is the leader. He is usually a man and enjoys the privilege of varying the prescribed steps and even breaking away from the other dancers and going through intricate gyrations involving graceful leaps and beats of the heels with the right hand. The leading position is usually assumed by each one of the dancers in succession.

The music of the dance is provided either by musicians sitting or standing nearby, or by the dancers themselves, in which case the verses of the songs are sung one by one first by the leader and then by the other dancers.

The names of the various dances are determined by a wide variety of factors such as tempo, degree of liveliness, place of origin, name of accompanying tune, historical or legendary event or action discribed by the dance, etc.

The dances of the ancient Greeks, depicted on classical vase paintings and friezes, or described by classical authors present many analogies to modern Greek folk dances. For instance, the modern Greek dance called Syrtos is strikingly similar to an ancient Greek dance of the same name mentioned in a Boeotian inscription and described by various ancient authors.

The following quotation, taken from Chianis' ‘Folk songs of Mantineia’, furnishes an appropriate conclusion to this brief introduction. ‘Surveying the folk music of Greece... one cannot fail to recognize the supreme position the music occupies in the villages. In its simple and uninhibited method of expressing love, patriotism, natural phenomena, happiness, or profound sorrow, folk music is an inseparable element of peasant life. As one peasant so aptly expressed: Our songs, like the sun, are our life’.

Markos Ph. Dragoumis (1980)

The expression syrtόs is found for the first time in an inscription from the 1st century A.D. which was discovered at the temple of Ptόos Apollo in Boeotia, near Delphi. It says: ‘.... he performed his forefathers' dragging (syrtόs) dances with piety’. This text indicates that syrtόs must have been the name of a traditional dance.

Syrtós is danced all over Greece and exists in two variants: Syrtόs in two (double step) and syrtόs in three. Syrtόs in two is danced quickly and has twelve steps. Syrtόs in three is danced in a slower rhythm and has only six steps: three stamping steps forwards, one step in the air and two steps backwards. The dancer stops after the third step, hence ‘in three’.

The syrtόs dance is lively and gay when it is danced on the islands, while on the mainland it has a slower, heavier and more masculine character.

Among jumping dances (pidichtós) can be mentioned tsámikos (3/4-3/8 south-west Greece) and pentozális (Crete), which previously ware danced chiefly by men, since they were originally considered to be war dances. There is evidence that the Cretans danced their pentozális wearing their full war equipment.

Most of the dances are group dances in which the dancers hold each other's hands. In some dances, however, they grip one another by the shoulder or the belt.

There are also dances which are danced two and two, in pairs or opposite each other. Examples of these are the ballos dance from the various islands, a typical pair dance in four time, and the so-called andikristós dance (‘facing’ dance), usually in 9/8 time.

There are also dances which are performed by a single dancer, e.g. drepáni (‘cut’) which imitates the reaper's movements, tatsá and zeimbékikos.

As regards the character of the dances, there are different categories according to the context in which a dance can originate and be performed. There are ceremonial and ritual dances, such as anastenáriki (‘the sighing people's dances’) which are performed in a state of ecstasy by shamans treading on burning coals on 20 and 21 May, i.e. St Constantine's Day and St Helen's Day. The dances take place in several parts of northern Greece where there are refugees from eastern Thrace. The shamans, carrying the saints' icons, leap barefoot on to the coals, singing, after having danced in procession through the villages.

There are also carnival dances, such as the gaitanáki, ‘merry-go-round’ (Thebes, Rhodes); boulles (Naoussa, northwest Greece), a parody of a wedding procession; and the humorous and very phallic dance ‘that's how you grind pepper’, to be found in different variations all over Greece.

There are also mimicking dances, e.g. the trata dance from Megara, near Athens. The dancers mimic the movements of a group of fishermen as they haul their nets out of the sea. Another mimicking dance is ‘the hare's dance’ from Thrace, in which two dancers perform the parts of the hare and the hunter.

The so-called ‘labyrinth’ dances have also been preserved up to the present day, among them tsakónikos (Kynouria in the Peloponnese), kangeleftos (lerissos in Halkidiki, tapinós (Thrace) and kotsangél (Pontos on the Black Sea). These labyrinth dances, with their winding, rhythmical movements and figures perhaps reproduce Theseus' procession through the labyrinth in Crete. An interesting point is that in a labyrinth dance it is young men who hold each other's elbows. The leader of the dance, however, is a grown man who ‘leads’ the youths into the labyrinth. This dance form has a possible direct reference to rites of initiation. The same type of dance is described as geranos (‘crane dance’) in Plutarch (46-120 A.D.), Lukianos (300 A.D.) and Eustathios (1300 A.D.) and is to be found in a number of vase paintings.

As regards labyrinths, it is worth noting that such constructions, made of stones placed close together, are to be found on the shores of Northern Europe. Researchers say it is almost certain that these too have been places where dances were performed, as their names sometimes intimate - Steintanz or maiden dance.

The idea with a labyrinth dance is that the dancers shall reach the girl at the centre of the labyrinth. It is a matter of dispute as to whether these labyrinths found their way north from the Mediterranean or whether the influence of the same migration - at the same time and independently of each other - brought these dances to both the Mediterranean and Northern Europe.

The dances are usually accompanied by various instruments. If instruments are lacking, the dancers can sing or clap their hands.

Certain combinations of instruments are typical of certain areas, e.g. the lyre and dairés (large tambourine) of Macedonia, the lyre and lute of Crete. The best-known combinations are: zijá (=pair, i.e. two instruments) violin and lute on the islands, zournás (shawm) and daouli (large drum) on the central mainland, and kompanía (from the Italian word compagnía) clarinet, violin, lute and santouri (cimbalon).

The combination zournás-daouli or pípiza-karamouza-daouli is best suited for out-of-doors owing to the very sharp and penetrating tone. It may however be replaced by kompanía, with or without singing, sometimes with more, sometimes with fewer instruments, but without changing the classical combination (clarinet, violin, lute, santouri).

Yulie Papatheodorou (1980)

The trilingual booklet of the LP, in Swedish, Greek and English (pdf)

Credits

Production team

- Domna Samiou (Research, Collection, Musical supervision)

Booklet team

- Markos Ph. Dragoumis (Texts and commentaries),

- Yulie Papatheodorou (Texts and commentaries),

- Zannis Psaltis (Texts and commentaries)

Singer

- Domna Samiou (Let My Eyes Go See, I’ll Be the Basil by Your Window, Why Did I Fall in Love With You?, When I Was a Lad, I’ll Jump From the Railings, Samarina, Our Tráta All Tattered, My Heart-Sick Bird Flown Far From Home, My Heartless Love),

- Apostolos Kyriakakis (The Brave Man, Kondylies)

Choir

- Greek Folk Dance Group ‘Eleni Tsaouli’ (I’ll Be the Basil by Your Window, When I Was a Lad, Our Tráta All Tattered, May)

Clarinet

- Petros Athanasopoulos-Kalyvas (Let My Eyes Go See, I’ll Be the Basil by Your Window, Why Did I Fall in Love With You?, Hassaposerviko, Samarina, My Heart-Sick Bird Flown Far From Home)

Flute

Pipiza

Violin

- Stefanos Vartanis (Let My Eyes Go See, I’ll Be the Basil by Your Window, Why Did I Fall in Love With You?, Hassaposerviko, Violin Solo, Samarina, Our Tráta All Tattered, My Heart-Sick Bird Flown Far From Home, May, My Heartless Love)

Cretan lyra

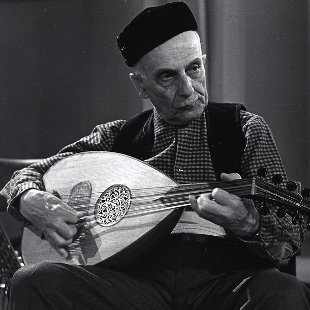

Oud

Lute

- Petros Athanasopoulos-Kalyvas (The Brave Man, Kondylies, May),

- Christos Athanassopoulos-Mortakis (Let My Eyes Go See, I’ll Be the Basil by Your Window, Why Did I Fall in Love With You?, Hassaposerviko, Samarina, Our Tráta All Tattered, My Heart-Sick Bird Flown Far From Home, My Heartless Love)

Daouli (davul)

Toumbi

Goblet drum

- Andreas Pappas (Why Did I Fall in Love With You?, Hassaposerviko, Our Tráta All Tattered, May, My Heartless Love)

Tambourine

Member Comments

Post a comment

See also

Song

A Cretan Ship

Song

A Maid Bidding Farewell

Song

Dawn Glowed in the East

Song

Exile Is the Greatest Hardship

Song

Forgetful, I Am Truly Glad

Song

I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height

Song

My Love-Bird Far Away from Home

Song

The Ship Is My House

Song

Turtledove

Song

Well Met

Song

When You Go off to Foreign Lands

Song

You Drive Me Mother out from Home