You are at: Home page Her Work Discography Akritic Songs

Akritic Songs

Contents

Akritic songs, which are perceived as the oldest examples of Greek popular poetry, are inspired by the legends of Akrites’ lives and their fights in defence of the eastern borders of the Byzantine Empire. The LP was recorded by the French Radio, published in Ocora series and distributed along with a successful concert of Domna Samiou in Saint Denis in Paris in June 1982. [Original name of the LP in French ‘Chants des Akrites’.]

Side A

- Production: Ocora

- Year of release: 1982

- Type: LP

- Production Country: France

Notes

One of the richest in the world as regards rhythmic and melodic variety, always vitally alive among a people who cultivates it in all its forms, Greek traditional music remains virtually unknown or misunderstood by the general public. Most of the recordings to be found in record stores represent only what is considered "commercial": dubious versions of various Greek songs and dances and, above all, those languid arpeggios strummed by professional bouzouki players for the sake of the customers of the travel agencies.

But Greece is in the first place the land of the Greeks before being that of the tourists. Its music is above all the music of non-professional singers and musicians, like those gathered together for the present recording around-the grande dame of Greek traditional song, Domna Samiou. Along with their art they transmit to us the message of a civilization and a culture which have managed to survive the passing of centuries and continue to mark the everyday life of today. The Songs of the Akritai which are performed here, poems and melodies that are over a thousand years old, have come down to us not as relics of a long lost past but as an aspect of a vigorous and fertile present.

The Akritai and their songs

In 717 the Byzantine Emperor Leo III forced the Arabs back to the banks of the Euphrates and assured the protection of the Asiatic frontiers of the Empire by settling warrior farmers called the Akritai (from Byzantine Greek : Akres = frontier) along them. Recruited from the plebeian sections of the cities, these men thus found themselves in faroff provinces charged with the mission of defending the border regions of the Empire from invasion. Provided with land and receiving pay exempt from any form of taxation, these warriors very soon constituted an important military force and became a threat not only to the enemy but also to the central power of Constantinople. In fact, the Akritai often rose in revolt against the Emperor and the great Byzantine landowners who coveted their lands, thereby gradually transforming themselves into autonomous chieftains and even participating in the court intrigues to overthrow one or other of the Emperors. The progressive disappearance of the Akritic military corps began around 1280 when Constantinople decided to abolish their fiscal privileges and to replace these formidable warriors by regular military units.

Created between the 8th and the 13th centuries, the so-called Akritic songs were inspired by great military feats, heroic enterprises and by the daily life of these warriors posted along the borders whose legend has continued to beguile the Greek people down to the present day. The heroes of these songs and ballads are not hewn according to the measure of ordinary men; they are described as superhuman beings bearing arms that an ordinary mortal could not even lift or mounted on supernatural steeds that feed on rocks and iron. What is more, the Akritas went into battle and fought against thousands of the enemy alone; his strength and courage were inexhaustible and he died only after a doughty struggle against Charon who was the personification of Death.

Born in the frontier provinces of the Empire, the songs about Akritic life spread throughout almost the whole of the Greek world, especially during the conquest by the Seljuk Turks of the Eastern regions of Asia Minor which forced the Greek populations to take refuge in the Dodecanese, Cyprus and in Crete (11th cent.). Because of their contents which exalted the struggle against the invader, the Akritic songs managed to survive throughout the long Turkish occupation of Greece (15th- 19th centuries) and to give rise to numerous variants.

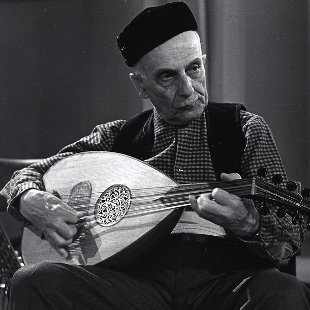

From a musical point of view, the Akritic songs are not very different from other traditional songs from the same regions, at least as regards their melodic structures. But the instrumental accompaniment, when there is one, is generally much more austere, doing no more than underlining the song and abstaining from all ornamentation of virtuosic demonstration. The evocative power, the reconstitution of the special atmosphere of each poem, and the ability to capture the attention of the audience are achieved solely by the voice of the singer.

Domna Samiou and the recording

A folk-musician since her childhood and a singer whose vocal potential adapts itself to the particular demands of the traditional repertory of virtually all the regions of Greece, Domna Samiou is able to assemble around herself the best singers and instrumentalists, whether they be professional or not. The reason for this is simple: the musicians recognize in her one of their own. They respect her not only for her great talent, but also because she has devoted her life to traditional music, scouring the entire country, seeking out and recording the best musicians, studying their techniques, rescuing hundreds of songs from oblivion.

For this recording Domna Samiou has called upon non-professional musicians coming from the regions where the Akritic songs that were selected originated. In the accompa-niments the choice of instruments respects the spirit of each poem and the musical traditions of the geographic region in which it was born. Thus, for example, the two songs from Pontus (southern shore of the Black Sea) are accompanied by the kementze (an oblong version of the Turkish kemençe) those from Thrace by the ga'ida (bagpipe) and the toubeleki (percussion), those from Cyprus by the violin and the lute, and the song from the Peloponnese by the shepherd's flute and the lute. The Akritic poems from Crete and Cappadocia are unaccompanied.

Aris Fakinos (1982)

Translated by Derek Yeld

Une des plus riches au monde sur le plan de la variété rythmique et mélodique, toujours vivante au sein d'un peuple qui la cultive sous toutes ses formes, la musique traditionnelle grecque reste méconnue ou mal connue du grand public. La plupart des enregistrements, que l'on peut trouver chez les disquaires, ne présentent que ce qui est considéré comme "commercial": des versions frelatées de divers chants et danses de Grèce et, surtout, ces arpèges langoureuses que des musiciens salariés égrènent au bouzouki électrifié à l'intention des clients des agences touristiques.

Vais la Grèce est d'abord le pays des Grecs, avant d'être celui des tounstes. Sa musique est avant tout celie de chanteurs et de musiciens non professionnels, comme ceux qu sont réunis sur ce disque autour de la grande dame du chant traditionnel grec: Domna Samiou. En même temps que leur art, ils nous /rent le message d'une civilisation et d'une culture qui ont su traverser tes siècles et marquer encore la vie ouotidienne d'aujourd'hui. Aussi les Chants des Akrites interprétés ici, poèmes et mélodies plus que millénares, nous sont-ils transmis non pas comme des créations d'un passé perdu, mais comme des aspects d'un présent vigoureux et fertile.

Les Akrites et leurs chants

En 717, empereur de Byzance Léon i repousse les Arabes vers les rives de Euphrate et entreprend de protéger les frontières asiatiques de ' Empire en y installant des agriculteurs guerriers, appelés Akrites (en grec byzantin Akrès = frontières). Recrutés dans la plèbe des cités, ces hommes se retrouvaient ainsi dans des provinces lointaines, ayant comme mission la défense des zones frontalières de l'Empire contre les invasions. Pourvus de terres, recevant une solde et exempts de tout impôt, ces guerriers ne tardèrent pas à constituer une force militaire importante et à devenir une menace non seulement pour les ennemis, mais aussi pour le pouvoir central de Constantinople. En effet, les Akrites se révoltèrent souvent contre les Empereurs et les grands propriétaires byzantins qui convoitaient leurs terres, se transformant ainsi peu à peu en chefs autonomes, prenant même part aux intrigues de la cour pour renverser tel ou tel empereur. La disparition progressive des corps militaires akritiques commence autour de 1280, lorsque Constantinople décide d'abolir les privilèges fiscaux des Akrites et de remplacer ces redoutables guerriers par des unités militaires régulières.

Créés entre le VIIIe et le XIIIe siècle, les chants dits akritiques s'inspirent des hauts faits militaires, des entreprises héroïques et de la vie quotidienne de ces guerriers postés aux frontières, dont la légende continue à séduire le peuple grec jusqu'à nos jours. Les héros de ces chants ne sont pas taillés à la mesure de l'homme. Ils sont décrits comme des êtres surhumains, portant des armes qu'un homme ordinaire ne pourrait soulever ou montant des chevaux surnaturels qui mangent des pierres ou du fer. Ajoutons que l'Akrite qui part à la guerre lutte tout seul contre des milliers d'ennemis, sa force et son courage sont inépuisables et il ne meurt qu'à la suite d'un dur combat contre Charon qui est la personnification de la Mort. Nés dans les provinces frontalières de l'Empire, les chants qui décrivaient la vie akritique se propagèrent un peu partout dans le monde grec, surtout lorsque les Turcs Seldjoukides conquirent les régions orientales d'Asie Mineure, obligeant ainsi les populations grecques à se réfugier dans le Dodécanèse, à Chypre ou en Crète (XIe siècle). A cause de leur contenu qui exalte la lutte contre l'envahisseur, les chants akritiques réussirent à survivre pendant la longue occupation de la Grèce par les Turcs (XVe - XIXe s.) et à donner naissance à de nombreuses variantes.

Sur le plan musical, les chants des akrites ne présentent pas de grandes différences par rapport aux autres chants traditionnels qui proviennent des mêmes régions, tout au moins au niveau des structures mélodiques. Mais l'accompagnement instrumental, quand il existe, est en général beaucoup plus sobre, ne faisant que souligner le chant et s'abstenant de toute ornementation ou démonstration de virtuosité. La puissance d'évocation, la reconsti-tution de l'atmosphère particulière de chaque poème, ainsi que le pouvoir de capter l'attention de l'auditoire passent uniquement par la voix du chanteur.

Domna Samiou et l'enregistrement

Musicienne populaire depuis son enfance, chanteuse dont les possibi-lités vocales s'adaptent aux exigences particulières du répertoire traditionnel de presque toutes les régions de Grèce, Domna Samiou peut réunir autour d'elle les meilleurs chanteurs et instrumentistes, professionnels ou non. La raison en est simple: les musiciens reconnaissent en elle une des leurs. Ils la respectent non seulement pour son grand talent, mais aussi parce qu'elle a consacré sa vie à la musique traditionnelle, sillonnant tout le pays, repérant et enregistrant les meilleurs musiciens, étudiant leur technique, arrachant à l'oubli des centaines de chants.

Pour cet enregistrement Domna Samiou a fait appel à des musiciens non professionnels, originaires des régions d'où proviennent les chants akritiques choisis. En ce qui concerne l'accompagnement, le choix des instruments respecte l'esprit de chaque poème et la tradition musicale de l'espace géographique qui lui a donné naissance. C'est ainsi que les deux chants du Pont (côtes sud de la Mer Noire) sont accompagnés au kementzé (variante oblongue du kemence turc), ceux de la Thrace à la gaïda (cornemuse) et au toubéléki (percussion), celui de Chypre au violon et au luth et celui du Péloponnèse à la flûte bergère et au luth. Les poèmes akritiques de Crète et de Cappadoce sont dépourvus d'accompagnement.

Aris Fakinos (1982)

Credits

Production team

- Domna Samiou (Research, Collection, Musical supervision)

Booklet team

- Aris Fakinos (Texts and commentaries),

- Derek Yeld (English translation)

Singer

- Domna Samiou (Now the Birds...),

- Stavros Gryllakis (I Saw Some Black Smoke),

- Nikos Papavramidis (Amarandos Goes to War (Marandon), Digenes Rescues His Beloved),

- Christos Sikkis (The Four Palikari),

- Eleni Stratoudaki-Lazopoulou (The Combat and Death of Yannakos),

- Dimitris Theophanidis (The Widow's Son)

Choir

- Women's Group (Digenes Is Dying, A Young and Gallant Soldier)

Flute

Gaida (bagpipe)

Violin

Pontic lyra

Lute

Goblet drum

Informant (source of the song)

- Eleni Stratoudaki-Lazopoulou (The Combat and Death of Yannakos)

References