You are at: Home page Domna Samiou A Tale of a Life The Shack with Tar Papers

The Shack with Tar Papers

Text

My sister was born in the shack and so was I with the help of a midwife, as was always the case back in Asia Minor. There were no hospitals available or maternity clinics, only midwives helping women to deliver.

My memories from a very young age are of living in a shack. And not just us, but a great portion of the refugees from Asian Minor who were settled in Kaisariani, especially in the lower part of the neighbourhood, all lived in shacks. Each family got a shack, irrespective of how many members it had. One single room. I admit I don't remember quite how big it was. Four by four metres? Maybe three by four. I do not know, I was just a child. But I do remember it was just one single room.

The shacks were set in a row. If I remember correctly, there was ours, then aunty Elenitsa's next to it, then Mrs Vangelio's, after that Mrs Maria's, Mrs Archondoula's and then Mrs Olympia's. So there were six shacks on one side and six on the other. The shacks were separated from each other on the back side by a partition of wooden planks. So if someone snored in the shack behind yours, or the neighbour diagonally attached, we would hear it. And indeed any other sounds they may be making.

I remember that directly behind us lived a family. A daughter, a son and their mother, who it seems was having an affair with a gendarme. There was plenty of gossip about it. The daughter was young, around sixteen or seventeen and quite chubby, and they all used to live in the same room, the mother, the lover and the daughter. The son left home at some point. As a small child I would hear all the gossip, without really understanding what it all meant.

Next to our shack my father had constructed a small kitchen out of old oil cans. He had opened out the old cans and constructed a small kitchen, so that mother could cook there and we also used to use it as a dining area. She also kept a tub there, and every Saturday she would wash us, as if she was doing laundry, my father, my sister and myself. She also had a large barrel in the kitchen, where she would collect rain water. Because the rain water was better for washing our hair and even the laundry came out better.

There was a family in our neighbourhood with eight children. The wife was called Costandia, and we used to call her Costandia the 'oil lady' (they used to make up nicknames), because she turned the little kitchen that her husband constructed into a small grocery, where she would sell oil. Imagine the space! In that small room, eight children and the two parents and the kitchen doubling as a store.

Many times we would put up in our little kitchen fellows or people from Asia Minor who didn't dare return to their houses further up because the police were after them, or there were road blocks and the like. Purely politically motivated, because they were communists. These people lived higher up in our neighbourhood, also in shacks, and would go to work as normal. But before returning home they would be warned, 'don't go up, there is a road block', so they would find somewhere lower down to spend the night, many times at our place. And because of the gendarme who used to stay right behind our shack my unfortunate father would tremble with fear. He used to tell me:

- 'Beware! Don't go out in the neighbourhood in the morning and tell the other children that uncle such and such stayed over the night.'

What I mean is that you could hear everything the way the shacks were built, and information would spread by word of mouth.

The shacks formed a rectangle, and there were narrow entrances through which only a bicycle or a donkey or at most a small cart could fit. But cars could not enter. In the middle of each rectangle there was a communal latrine, which was also separated in two, one side for women and one for men. Of course people were also obliged to use potties at night and the next morning all the women of the neighbourhood would march out to empty them in the latrines. There was a common drain were all the waste would collect, and the special disposal truck of the municipality of Kaisariani would often delay coming to empty it, so it would fill up and overflow and smell.

There was no running water in our shacks of course. There were communal municipal taps on some corners, which were cemented around. I remember we used to go and get water. My poor mother would work to help out my father and would be away all day. Since the water only ran at certain hours of the day, let’s say from ten o'clock to noon or from one o'clock to three, everyone (but primarily the women) would rush out to fill their canisters. We would use old oil cans which had a piece of rounded wood fixed across the middle for a handle, or buckets. Since my mother was away at work and my sister was a seamstress's apprentice and was not home, I would usually have to carry water for my whole family. I can remember the scene when we used to queue up. The women would get up early and go and place their cans in a queue, one behind the other. When the water would come, we would go to the tap and of course sometimes someone would try to queue barge. Then fights would break out with the canister being brought down on each others heads. There was also an Armenian woman whom we had nicknamed 'the burned onion', because she would come with her canister and plead with us to let her get water, with the excuse that she had left onions cooking on the fire and they would soon burn.

Until 1940 – 41, when the German occupation started and I left home, but even as late as 1944 when my whole old neighbourhood got burned, I never heard that they had put running water in the houses. The same must have applied for the other neighbourhoods above ours, which we used to call the 'built ones', since above a certain point, although they were still refugee houses, they were built with adobe bricks. Some were single storied and some double storied. They still exist even today, but I am afraid that soon they will knock them down to build apartment blocks. Even now I often pass by or go and visit them. I am always deeply moved. And those 'built ones' as we called them had a similar system to ours: very small rooms and outside tiny kitchens that you have to bend down to enter. I wonder how these people fit in them. So I am afraid that those people too had no comforts.

Further up from us there was a ravine which has now been covered over. That was the Armenian quarter. There was an Armenian church, with an Armenian priest, and in it the Armenians ran their school. And we were total brats. When we would go by, we would tease the Armenian children. I remember the Armenian priest, who used to come and visit a family which lived close to us. I don't remember exactly when, but at some point the Armenians all left as a group and went to Russia. At least that is what I heard. Close to the ravine there was also a small factory where the Armenians made rugs, and as I would pass the ravine on my way to school, there would be green and red dies spilled everywhere.

The Shack with Tar Papers

Images

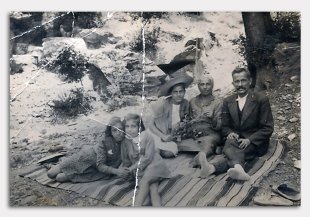

01 The Samiou family on the 1st of May in Kaisariani, 1939

Domna, cousin Despina, Chrysa, Maria and Yannis

© Domna Samiou Archive

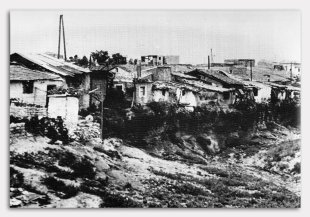

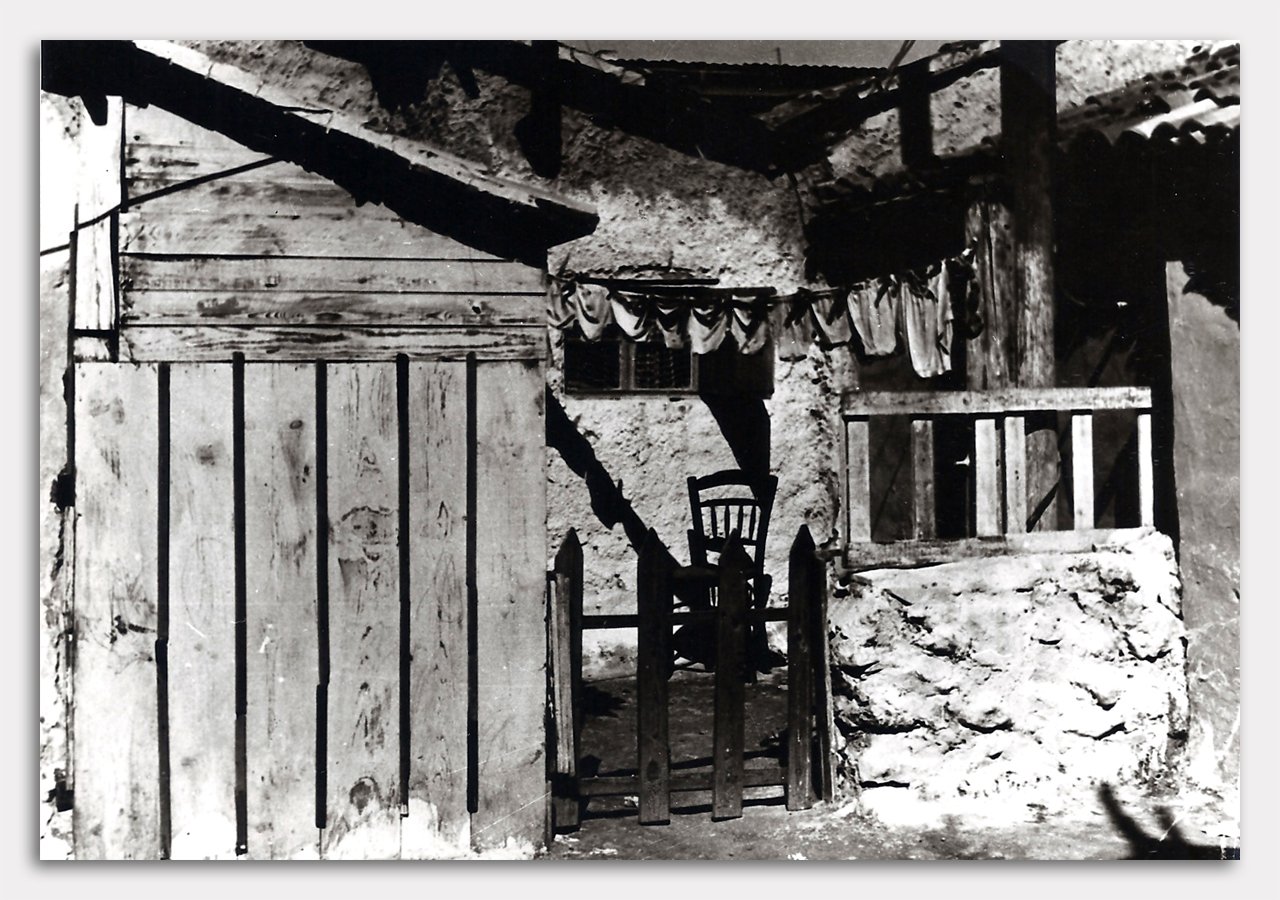

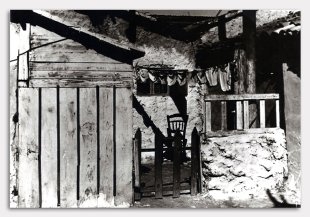

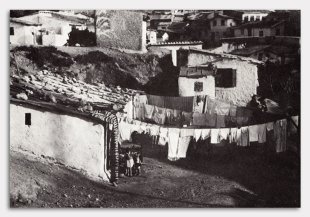

02 Kaisariani, refugee shack

photo Elli Papadimitriou

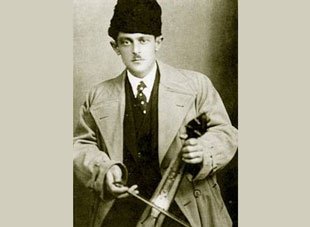

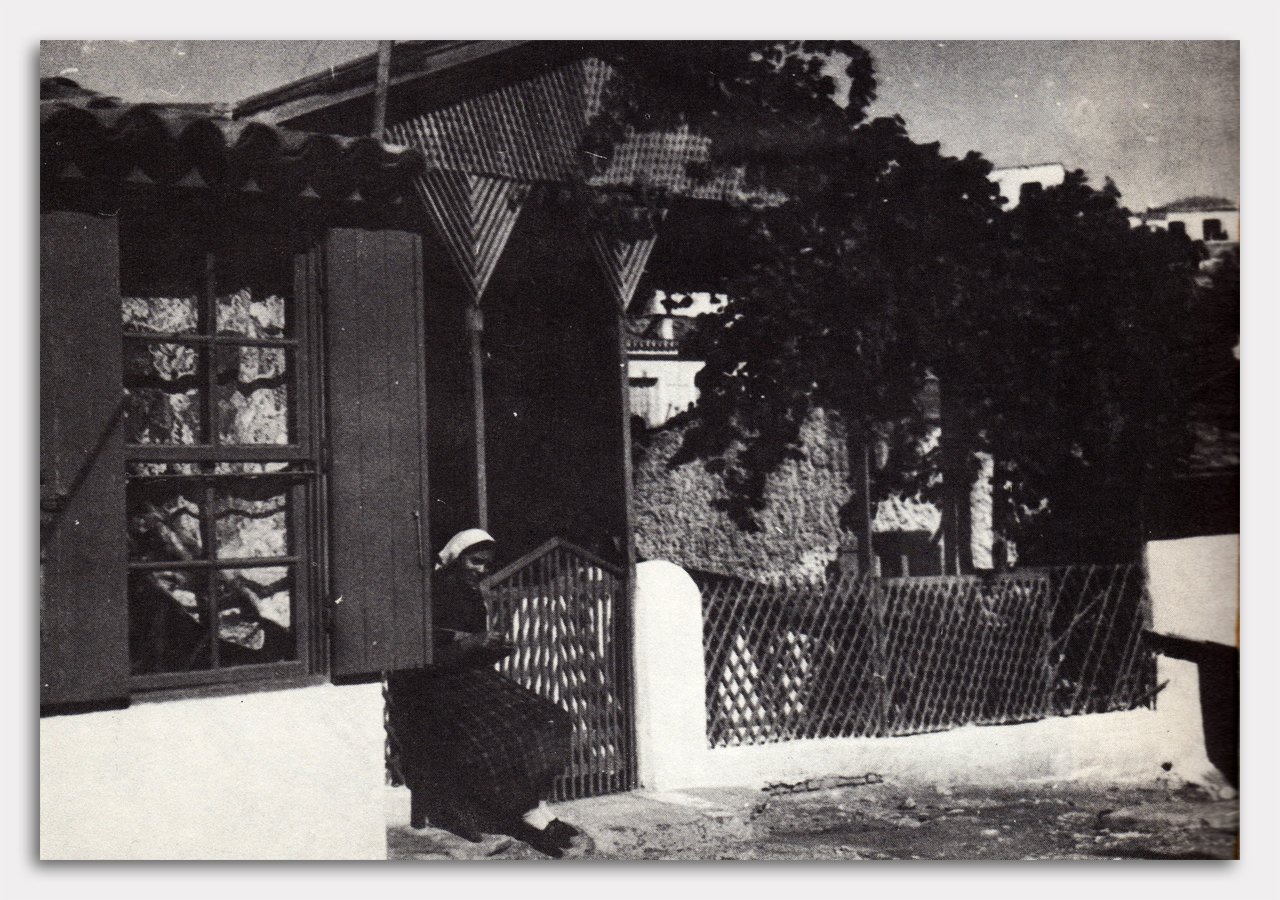

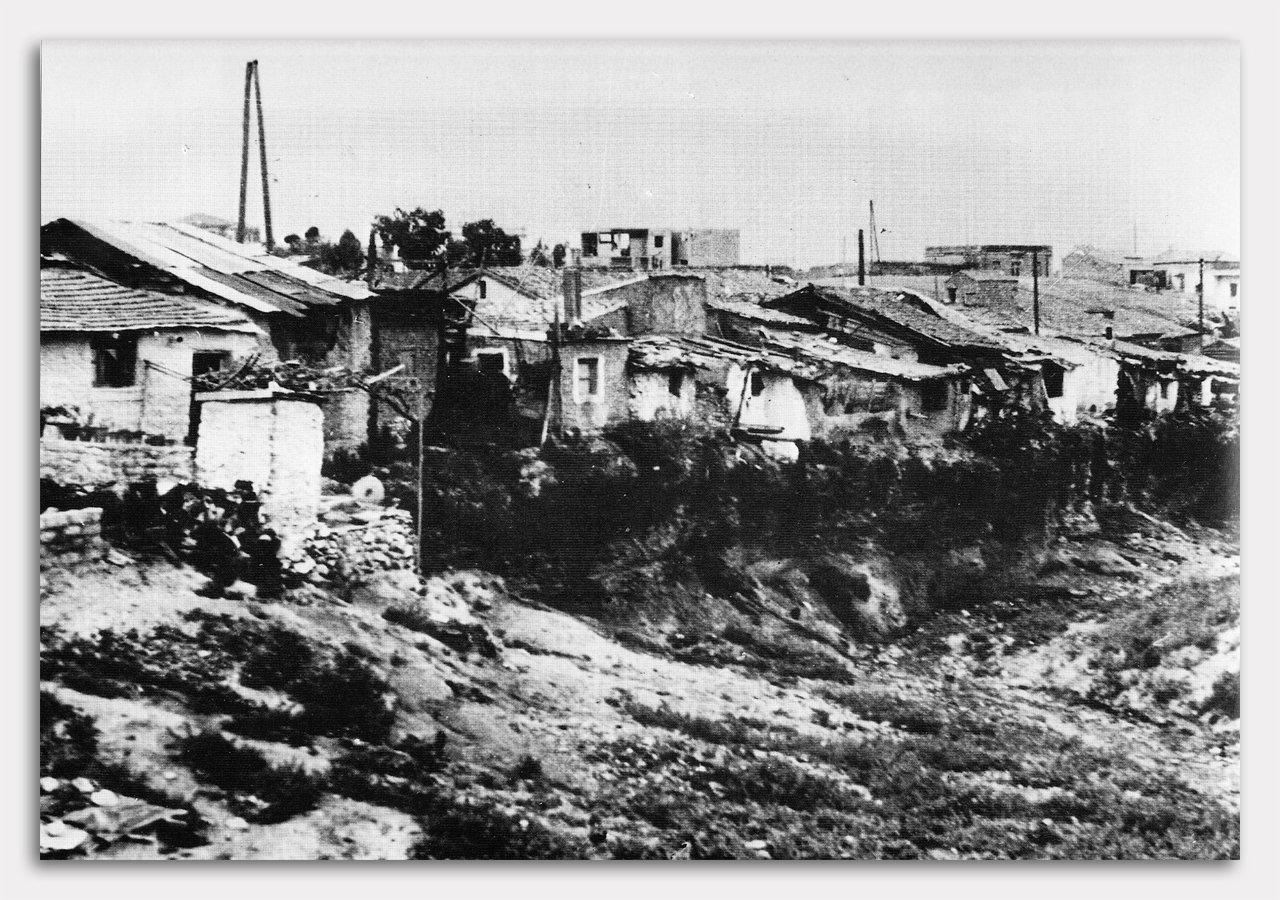

03 Kaisariani, 1940s

photo Elli Papadimitriou

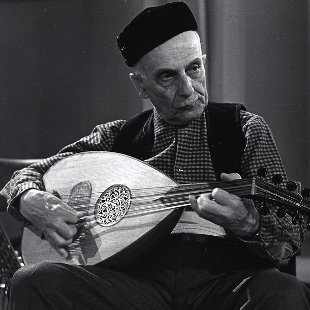

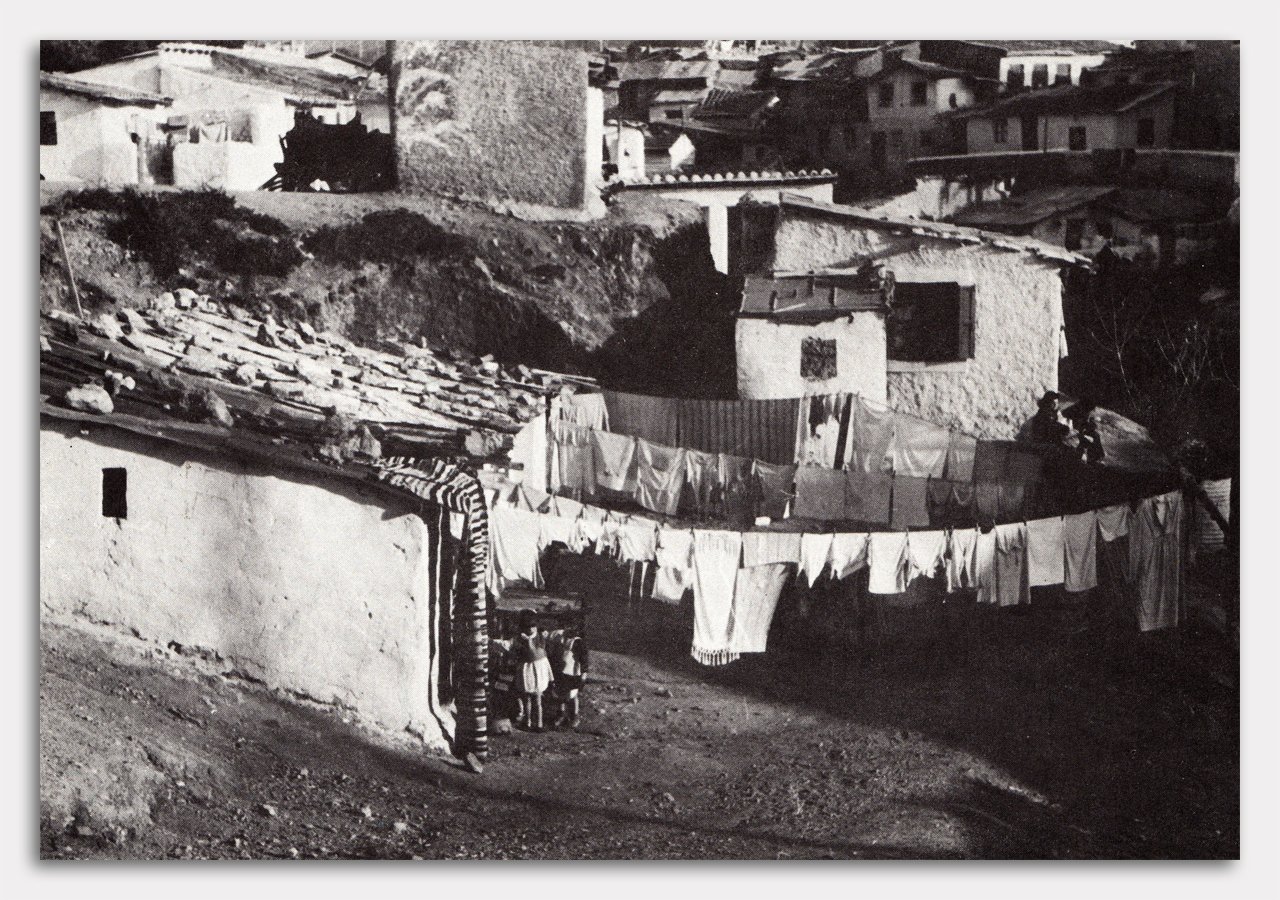

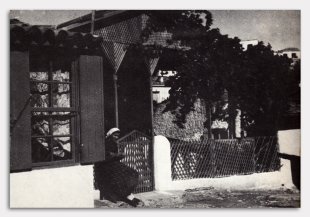

04 Kaisariani, 1950s

photo Elli Papadimitriou

05. Kaisariani, 1950s

photo from Spyros Tzokas' book 'Καισαριανή: Η φυσιογνωμία μιας πόλης', Athens 1998