You are at: Home page Her Work Discography Songs About Greeks Far From Home (LP)

Songs About Greeks Far From Home (LP)

Contents

This LP includes nineteen songs narrating all the different aspects of migrating in foreign lands: the departure and the life to foreign lands, the life of the family left behind, death in these foreign lands or the return home. This publication of the UNHCR, with its informative accompanying booklet, introduces a new orientation in Domna Samiou’s music publications: from now on all records published by her Association will be thematic and always complemented with extensive documentation.

(barcode: 5204910001811)

Side A

Side B

Side C

- Production: UNHCR - The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Year of release: 1989

- Type: LP

- Sponsors: Songs of Dame Sea

- Production Country: Greece

Notes

A sense of nostalgia - the pain of separation and the desire for the home-coming (νόστιμον ήμαρ : the day of return) - persists throughout the centuries in every form of popular and cultivated literature: in antiquity (the Homeric epics, lyric poetry, ancient drama), in the middle ages (Byzantine epic poetry, popular ballads, metrical romances), and in modern times (demotic songs, folk tales and fables, proverbs, literature and poetry). It is not without significance that in common parlance the word νόστιμον has come to mean something pleasant, palatable, agreeable, while ξένος (foreign) has become synonymous with ugly, troublesome, unfortunate.

The foreign lands and deprivation, bitterness and Charon,

they put these four on to the scales, the foreign lands weighed heaviest.

Demotic songs about having to live in foreign lands belong to one of the most interesting categories of neohellenic folk poetry. This is so because, apart from their literary value which is connected with the more general style of the demotic song, an historical and anthropological approach to them is especially revealing in terms of the actual circumstances in which they have come into being, of the occasions on which they are sung, and of the extension of their applications.

Indeed, any study along these lines provides exceptionally rich material for the analysis of popular philosophy, ideology, and social behaviour in the modern age of Greece: how collective knowledge and memory confronted by a central, and frequently unavoidable, social phenomenon such as migration range themselves before it, and how the people's general consciousness and interpretation of the world in relation to the practical and ethical consequences of the phenomenon are given expression.

Despite the obvious truth that certain poetical motifs have a much older origin (such as the subject of the exile's home-coming A fair Trikeriotissa), the historical period in which most of the songs concerning migrant Greeks were composed coincides with the Turkish invasion and occupation of Greece (14th to early 19th century) and with the demographic, economic, and social impact these had upon Hellenism.

The more recent great migration movements towards the Americas - the USA, Canada, and South America - dating from the end of the 19th century, and towards Australia and the countries of Western Europe, mostly since the second world war, have not produced similarly remarkable examples of music and poetry. The circumstances in which popular creativity had to function changed with the foundation of the modern Greek state. Originality disappears after the mid 19th century: old poetic motifs and themes are adapted to contemporary conditions and popular melodies are simply reworked to suit the more modern musical instruments - klarino (clarinet) and violi (violin) - which have intruded from the West and displaced traditional ones like the zournas, phloyera, tsambouna, and lyra. Finally, there are the curiously few postwar songs about Greeks living abroad (such as ‘In Germany's great factories, and in the Belgian coal - mines'): their framework is the more recent urban music by named composers which came to the forefront following the decline of rebetico songs in the '50s and '60s; it no longer has much to do with earlier forms of music in this category. For this reason all the songs selected for this collection belong to the classical period of demotic song, in which later urban and Western influences are not so strong. In the course of time they have undergone a collective process involving the removal of redundant elements and the creative adaptation of what is alien or new to the traditional within this group. In this way they have been preserved through the years and continue to move both hearts and minds.

Ι want to lay a heavy curse on all three vilayets1 ,

on Constantinople, Bogdania, and also Wallachia,

for they play false with all our youth and give no thought to mothers.

The Turkish invasion of Thrace, Macedonia, Thessaly, and Epiros, commencing in the 14th century, and the settlement of colonists drawn from warlike Mohammedan tribes in fertile and commanding districts caused a numerical decline and economic stagnation among the Greek population which then sought refuge or better conditions in less accessible mountainous regions or in Greek territories held by the Venetians, that is, in islands in the Aegean and Ionian seas. Conditions among indigent mountain communities, as also on most of the islands, barren and exposed as they were to piratical raids, were such that their members could provide themselves with only the bare essentials for existence. Very naturally they soon led to the first isolated or group instance of migration as well as to waves of refugee movements in the wake of devastating political or military upheavals. From the end of the 15th century, however, once the Turks had consolidated their conquests, people started, slowly at first, to leave their mountain fastnesses and, as the birth rate rose, the urban population began to grow. It was during this period that commercial transactions and trade began to blossom because of the new circumstances prevailing in Europe where Greeks, ever tireless travelers, bold seamen, and clever entrepreneurs, were called upon to play their part.

Thus from the 17th to the 19th century Greeks gradually established themselves outside their own country, the diaspora extending to all points of the compass: Italy, Central Europe, the North Balkans, Russia, the Black Sea, the Caucasus, Constantinople and Asia Minor, Persia, Egypt, Corsica, Iberia, France, England, and Holland. From the 8th century of our era there had been a Greek quarter (Haret el Roum) in Old Cairo (Fostat). There are 18th-century references to a Greek school and church in Erzerum in Armenia, in Calcutta in India, and in Gondar in Ethiopia. The first Greeks to settle in Florida, in 1768, arrived there from Corsica and the Peloponnisos. In 1829 seven Greek sailors reached the newly founded settlement of Sydney in Australia.

Sleep on, I've given orders for your dowry from the City 2,

I've sent away to Venice for your dresses and your jewels.

The Greeks have always had particularly close ties with Italy, even in antiquity through their colonies in Magna Graecia.There are records of Epirots living in Livorno, Naples, Sicily, and Venice in the 11th century. A growing number of Greeks settled in the latter city, especially after the Turks had captured its possession in the Peloponnisos in 1540 and after they had taken Cyprus in 1571. By 1585 they numbered 15.000 and fifteen to twenty Greek vessels were visiting the port every month. It was about this time that the Greeks wrested a considerable portion of the trade conducted throughout the Balkan peninsula by local Genoese and Armenian merchants who had dominated the market till then.

While George Sinas was monopolizing communications throughout the Austro-Hungarian empire, and thus acquiring the stature of a magnate, more and more Greeks were heading for Moldavia (the Bogdania of the songs) and Wallachia (Bucharest and Iasi).This movement intensified after 1711 when Phanariots, members of leading Greek families in the Phanar district of Constantinople, were appointed as local rulers. The Greek element in Russia - in Odessa, Moscow and Petrograd - was strengthened by the privileges granted by the empress, Catherine the Great, following the abortive Orlof uprising of 1770 when refugees from the Peloponnisos and the islands established exclusively Greek villages in Tiflis, Kerets and Taganrog.

See how in distant foreign lands they get along and manage,

see how they wrest a living there, and see what tongues they speak.

Geek colonies soon organized themselves into communes and the merchants into associations (kompanies). The first Greek news- sheets came off printing presses in Vienna and Venice where a remarkable publishing industry sprung up, while the great teachers of the Greek Enlightenment, such as Anthimos Gazis, Konstantinos Koumas and Neophytos Doukas, taught in the community schools in both cities. It was not long before this activity brought evident results, migrants and travelers becoming the vehicle of the new spirit they found abroad, transmitting to Turkish occupied Greece the messages implicit in the European movements directed towards wider economic, cultural, and political horizons. Impoverished mountain communities were revitalized: on Mount Pelion, in Epiros and in Western Macedonia costly mansions were erected with wall-paintings and richly carved interiors; in the islands the motley of clothing, the jewelry, furniture, and ornaments brought back by mariners gave a new direction to local popular arts. It is a fact that the greatest benefactors of the nation came from the Greek diaspora, most of them originally from Epiros which, together with Macedonia, supplied the majority of the migrants to Wallachia (Zappas, Arsakis), Austro-Hungary (Sinas), Russia (the Zosimadis brothers, Varvakis, Rizaris, Kaplanis), Egypt (Tositsas, Stournaras, Averof), and Constantinople (Zographos).

The Greeks' aptitude for language was enhanced and new words were introduced into local dialects. Liberal ideas paved the way to the Revolution of 1821 and to national independence. Rhigas Pheraios moved from Moldavia to Bucharest and published his patriotic songs and great map of Greece in Leipzig and Vienna (where there is still a Griechengasse today), while the Philiki Etaireia (Society of Friends), founded in Odessa in 1816, was to give the signal for the Greek uprising.

The time has come for us to leave, it's time for our departure.

Besides the flow of Greeks emigrating for a long while to join the prospering Greek communities in central Europe and the Balkans - the dream goal of all who wanted to leave so as ‘to bring back florins on their mules, and piasters on their horses' - there was also a seasonal migration with the object chiefly of acquiring necessities for the harsh winters in mountainous regions. Builders from the 'artisan villages' of Western Macedonia, from Zagori in Epiros, and Langadia in the Peloponnisos and also seasonal workers (among them carpenters, coppersmiths, tailors, herdsmen, harvesters and vintagers) journeyed to Thrace and Constantinople and farther still to Sofia and Bucharest, as well as to Asia Minor, seeking work alongside similarly motivated migrants of other nationalities: Albanians, Turks, Serbs, Croats, Jews, Armenians and Bulgars. It was their dream, too, to find favourable conditions somewhere where they might settle and so one day summon their families to join them or where, in some instances, they might marry, an event treated in song as a grievous betrayal (songs A cretan ship, White doves o mine, white ring-doves).

Such seasonal migrations were usually confined to the period bounded by the feastdays of the two great saints, Saint George (23 April) and Saint Dimitrios (26 October). In the words of a typical song from Macedonia:

‘Saint George and Saint Dimitrios fell out with one another.

- Saint George, you family scatterer, good George, you fearsome fellow,

I bring together families and you go scattering them,

I gather mothers with their young and goodwives with their husbands,

I gather loving couples, too, who love each other dearly...'

The Turks declared the same period to be free for navigation in their waters (during which, moreover, they pressed into their navy any Greek crews they could), while only a little earlier, usually during March, seafarers set out again on their voyages. Hence one song (I wish for all the months in turn) refers to March as the month that ‘fits galleys out for sea and slips a vessel's moorings'.

Good Rovas started out upon his journey to Wallachia,

full forty days, full forty days and nights he wended thither

until he reached Wallachia and wretched Bucuresti.

- I've brought one hundred lads to you, nad all from Yannina town.

In contrast with the seasonal migrants, most of the great caravans destined to Central Europe and the northern Balkans set out in September (usually on the 14th, Holy Cross Day). We know the names of some of the caravaneers (kyratzides): Rovas, Sinas (grandfather of the benefactor), Phetanis, Kiopekos, and others who appointed agents to assemble intending migrants from villages round about (song Forgetful, I am truly glad). The main starting-points were Yiannina, Divra (Zagori), Kozani, and Saloniki (Thessaloniki).

It was to these towns that Greeks living abroad sent their letters and money and gifts to be delivered to their villages by special ‘postmen' known as lartarides or amanatzides. Migrants' caravans comprised up to one hundred horses and mules, while commercial ones consisted of many more beasts of burden. The best animal (seraidaris or kalaouzos) took the lead and the caravaneer on his mount (beïnaki) brought up the rear. Sometimes two or three caravans linked up together, while wayfarers and members of seasonal gangs of artisans followed behind on foot or greater security from attacks by robbers, one of the chief troubles then confronting travellers. (Christos Christovasilis records instances of migrants arriving home destitute after robbers had waylaid them on their return journey and had seized everything they had saved up while working for years in a foreign country.)

The routes normally taken by caravans were these:

1 Yannina - Grevena - Kozani - Monastiri (Bitolia) - Skopje - Kumanovo -Belgrade (following the river vallies of the Aliakmon, Vardaris - Axios, Morava, and Danube).

2 Two routes led from Belgrade: one towards Budapest and Vienna and one towards Iasi and Bessarabia (now Soviet Moldavia), and Russia.

3 Yannina - Kozani - Saloniki - Serres - Constantinople - Philippoupolis - Sofia -Bucharest.

4 Another road led from Constantinople to Asia Minor (Brusa and Smyrna) and from there, via Tokat and Erzerum, to Persia.

The journey from Thessaloniki to Vienna took about thirty-five days, while the Yannina - Bucharest route was covered in forty to fifty. Travellers were on the road for eight to ten hours each day. They spent the nights at khans (inns) or, along the main routes, at caravanserai, most of which belonged to Epirots; the largest khan in Bucharest, for instance, was the Gretzi-Khani (that is, ‘of the Greeks'). Forty-five khans are recorded as lying along the route between Yannina and Constantinople; apart from providing shelter and food, they served as a kind of travel agency and as employment centers. Khans often gave their services on credit, migrants settling their accounts on their homeward journeys when eventually they returned kazantismenoi, in other words, with their purses full.

Songs also are composed of words, they're sung by those embittered,

they strive to oust their bitterness, but bitterness won't leave them.

There were periods when migration - a milestone in the life of a Greek - was an inevitable stage in his life-cycle (birth, marriage, migrancy, death), a stage predetermined by his fate within the limits of the roles he was called upon to play in his community.

Thus, in traditional society, ‘Migration came to be associated with any youth reaching manhood and thus being obliged to leave home and seek elsewhere his fortune and worldly knowledge - an event that acquired the character of a rite of passage. Like a birth or marriage or death, it was a turning-point in life, the point at which the individual passed from one social and existential condition to another, horn one country to another' (M. Terzopoulou - E. Psychoyiou).

There was nothing slight about the wish once uttered for newly-born or young Epirot children: ‘May he become a baker in the City (of Constantinople)'. For very often those children were destined to follow their elders from early on, from even only twelve years of age, in their search of fortune in a foreign land. Nor are I he poetic motifs, common to songs about both migration and marriage or death, quite fortuitous (see, for instance, the Pontic song about life away from home, (A cretan ship) known as katsangell' it is sung and danced at weddings at the moment when the mother-in-law ritually introduces the bride to her new home).

The departure of a family member, whether through marriage, migration, or death, was always a traumatic occasion within the close-knit unit of a traditional Greek family. And since the family is in fact crypto-matriarchal, it is the mother herself who undertakes in a ritual manner to 'banish' both her son to foreign lands (You scold me, mother out of home, You drive me mother out of home) and her daughter to an alien hearth, her husband's home or village (as one wedding song puts it: ‘One Friday and one Saturday evening, mother banished me...I leave weeping...') An entire ritual in which the kneading of bread-dough plays an important part is involved on both occasions of departure (Forgetful, I am truly glad). One of the resulting bread-loaves, scored with a cross, was preserved among the icons, while good fortune was invoked in various acts of sympathetic magic: a silver coin (a para) was inserted into the loaf handed to the migrant; on leaving he had to walk through a flock of white sheep, symbol of happiness; his last draught of water was drawn from the village well, and he cupped some of it in the palms of his hands and threw it behind him; and with his right foot he had to kick over a crock of wheat and coins as he emerged from his home, and then gather up both and take them away with him.

A curse upon the carpenters who build the sailing vessels,

in which young bridegrooms sail away and leave their brides a-weeping.

Songs about Greeks far from home are usually the creation of those who have been left behind, particularly the women folk, foremost among them being the mother and the wife or sweetheart of the migrant (a sister more rarely plays a part). The total absence of the father is wholly characteristic, as it is in all other cases of rides of passage in which the women predominate. In the poetic language of a traditional society the father may appear only in a strong and leading role. In the event therefore that he is unable to protect his family from the grievous consequences of migration he is excluded by the womenfolk, who impose their own sentiments, their own interpretation of the event, upon the song. For ‘if migration as a social occurence is the preserve of men, as a phenomenon subject to an individual's moral judgement in the name of the basic tenets of a popular society and of purely philosophic considerations it is the preserve of women' (Guy Saunier).

Thus the wife of a migrant, though at first she insists on his taking her with him to perform a wife's everyday chores (I wish for all the months in turn) or for companionship (When you go off to foreign lands), eventually submits lo his reply, ‘Where I am going, lissom one, no woman ever travels'. It was the same for the mother who had to ‘banish' her son so he should fulfil his role in society, though she might wish to thwart his departure (Forgetful, I am truly glad). Both of them, repositories of collective knowledge and memory, fear the outcome will be death (You drive me mother out of home) or, no less evil, ensnarement by another woman in a strange land and therefore mythicized in a negative manner.

Nevertheless, they are ready to acknowledge the material gains to be got from migration to a foreign country, indeed, in some songs the women compel the man lo return home and bring back his spoils (‘Go to the Polis's bazaars, and then to Saloniki / and bring a Frankish looking-glass and a hair-comb of ivory / bring copperas with you as well, so I may dye my tresses'). But being also the recipients of its harsh consequences, in the end they reject migration (‘May fire consume the florins up, and flames the goods he's gathered / I want my mate back home again, I want some play and laughter').

A curse upon you, foreign land, on you and all your doings,

you took my lad away from me and made him one of your sons.

Despite these familiar consequences, death and seduction, roles are pre-ordained and the dramatis personae are subject to them, just as their song underscores and prescribes their sentiments and reactions.

Any study focusing upon this aspect is particularly revealing of the inter -relationship of husband and wife, mother and son, mother-in-law and bride. There are verses in which an aggressive attitude may be detected (‘Dawn breaks upon the mountain tops while pretty girls are sleeping / and mother's sons in foreign lands are suffering oppression'); and others are play upon a mother's guilt for her sons migration and the hardships he undergoes, a guilt expressed in the wish that she had never given birth to him (Yorgalakis). Above all, however, there predominate the wife's sense of insecurity, her fear lest he have love-affairs, and the jealousy of other women felt by both wife and mother: ‘The first kiss only made him sigh, the second one ensnared him / the third kiss truly venemous, made him forget his mother'; or again ‘Whose husband's in Wallachia and son in Bucuresti / tell her not to expect them back, not vainly to await them / Vlach women are malicious ones with fine and curvy eyebrows / with eyes of olive hue and shape and brows resembling ribbons /They have eye lashes that are like the fiddlesticks Franks bow with'. They conclude with a heavy curse: 'A visitation of the plague on all Wallachian lasses' (also song I would I were a bird).

It was only to be expected that should the migrant fall for their charms, forgetting the mother and wife awaiting his return, the happening would be attributed to seduction, deceit, or magic in order to confirm the negative myths woven around the foreign land and particularly its womenfolk (A cretan ship and White doves o mine, white ring-doves in which the following distichs are sung: ‘I tightly saddle up my horse, it is at once unsaddled / I tightly buckle on my sword, it is at once unbuckled / I pen a letter to send home, the ink fades as I write it').

Mythicism attains monstous dimensions as that moral evil, the ‘uncleanness' of living in a foreign land, spreads until it invests every physical object (A cretan ship) : the migrant's kerchief dyes the river, the sea and the ships upon it, and whatsover fresh and green or vigorous (My love-bird far away from home) comes into contact with it (‘A mounted pasha passed that way, his horse was dyed all over / Also it chanced a bird flew by, its wings were dyed all over').

Could I but kneel before my sire, my mother's arms around me,

the hands of my beloved in mine, I'd lay me down and perish.

A tragic end to the fate of a migrant is his death in a distant country. At once harrowing and dishonourable, unattended as it is by any ritual, it is one of the most devastating of curses (‘...a foreign soil shall eat his flesh...'). The climax of the drama is the failure of the dead man to find repose, since the alien soil rejects him and desecrates his remains (Syrmatiko). Equally harrowing is the death of a seafarer far from his home, though the association of the Greek with sea is more familiar than with the foreign lands: the same waters break upon his island home and he always has his fellow seafarers to relieve his loneliness (There were three monks). Nonetheless, as Samuel Baud-Bovy has noted, the sea has inspired relatively few songs among the essentially maritime nation of the Greeks. The mountains, springs, and trees are very frequently referred to in demotic songs and lovingly, too, while on most occasions when it is introduced the sea evokes expressions of sorrow, separation, and bitterness (You quench your thirst... o sea).

I greet you, love, dear treasure-chest, with double locks protected;

I've been away these forty years, yet still she's waiting for me.

In most songs about life in foreign lands death is hinted at as a persistent threat, while the home-coming is never final but merely transient, an event that intensifies the pain of separation (‘You made me, mother, an ill match, you gave me to a Wallach / Twelve years he's in Wallachia, but three days in his home here'). An exception is to be found in the song ‘The return of the migrant', though it is connected with another category of popular airs, the ballads (paraloges). This is clear from their narrative character which does not recur in any other sons/s associated with Greeks abroad (their texts are generally of a lyrical and improvised nature, and thus variable in form). One of the oldest categories of Greek demotic songs, the ballad, has been the subject of numerous studies that have pointed to the similarities it bears to, for instance, the recognition scene in The Odyssey in which Odysseus is recognized by Penelope, but also with songs on the same theme sung by other European peoples, as well as with old Russian popular folk-tales (N. Politis, Samuel Baud-Bovy, S. Kyriakides, K.Romaios, I. T. Kakridis, D. Maronitis).

The migrant returns home in disguise, as did Odysseus on the oracle's advice, in order to verify his wife's fidelity. She does not recognize him, the natural consequence of a long abstinence during which his features have altered, an occurence often noted in the songs (‘I go up to my mother's door she looks at me and draws back / I then go over to my wife's, she does not recognize me'). The corroborative evidence is the same as in the Homeric tale: fruits of fertility (the apple and the grape), a particular room in the house (the bedroom), and physical characteristics. Moreover, identical words, the self-same lines, and similar expressions persuade one to the view of I. Kakridis: ‘There is a close inner association between The Odyssey and the song of the Migrant'.

Ballads (paraloges) of this kind, in the form in which we know them, date from the 9th century A.D. and originated in Asia Minor. With their distinct theatrical elements, such as setting and dialogue, they take their name from ancient drama and the parakatalogi, the recitation of the calamitous incidents in a tragedy, intoned to the accompaniment of a musical instrument. In one of the songs recorded here (A fair Trikeriotissa) all the verses are sung for the first time in recording history down to the point where most variations end: the recognition. Furthermore , it is worth noting one other significant aspect of this song: with the couple finding themselves together again, it continues more boldly, laying emphasis upon the couple's long abstinence from physical union: ‘Come, serving girls, come and assist, make up our nuptial bed / Three well-strewn pallets they deranged before the break of day / and yet another three deranged before the sun rose up / Christ, don't allow the cock to crow, nor yet the day to break / for, see, I hold in my embrace my white and gentle ring-dove'.

I know an oceanful of songs and choose the air that suits me.

Setting aside their historical and thematic content, the songs in this collection have been selected with an eye to including as many musical idioms from all parts of Greece as is practicable. The two songs (I wish for all the months in turn, A maid was singing longingly) from the Propontis are taken from the collection of Simon Karas' Society for the Dissemination of National Music, while melodies Yorgalakis and A fair Trikeriotissa were recorded by Domna Samiou in Keramidi on Mount Pelion and in Trikeri in Magnesia, respectively. The remainder come from various collections and private archives. An attempt has also been made to juxtapose verses from variants of the same song. Particular attention has been paid IO including a representative variety of scales, metrical rhythms, and musical instruments.

The scales of Greek popular music are modal and radically different from the diatonic scales of western music; they are distinguished by their use of intervals smaller than the semitone and by the arrangement of the intervals, which is different to that of the major and minor scales in the West. They are related to the harmonies of ancient Greece, the echoi (‘sound') of Byzantine ecclesiastical music, and the scales of oriental musical systems: the Arabic makams (‘roads'), the Persian dastgah, and the Indian ragas. Greek popular musicians use Arabic-Turkish terms to describe their scales. Noted below are their equivalents in Byzantine echoi, and their relevance to songs on these records:

Ussak - echos protos / (I wish for all the months in turn, You drive me mother out of home, I would I were a bird), Huseyni - plaghios tou protou (You scold me, mother out of home, A cretan ship, A maid was singing longingly). Rast -plaghios tou tetartou (You quench your thirst... o sea), Nigriz- - chromatikos plaghios tou tetartou (White doves o mine, white ring-doves). Hidjar -plaghios tou defterou (When you go off to foreign lands), Kurdi (A fair Trikeriotissa).

Two songs make simultaneous use of two different scales, moving from hidjaz to ussak (Yorgalakis), and from huseyni to ussak (Syrmatiko). The pentatonic anhemitonic scales (with five notes and no semitones ) of songs Forgetful, I am truly glad, Your kerchief, Yanni, and My love-bird far away from home are of particular interest. Studies carried out by Samuel Baud-Bovy reveal that these scales - found mainly in Epiros, in certain songs sung by Thessalian women, and in North Evia - have preserved into our own times the structure of the Dorian mode, the quintessentialy Greek ‘harmony' of ancient Greek music.

There are also two other elements found in songs in this collection that confirm the unbroken descent of Greek music from antiquity to the present day: the 7/8 rhythm and the iambic fifteen-syllable line. The panhellenic 7/8 rhythm (3+2+2) of the syrtos kalamatianos dance (White doves o mine, white ring-doves, I would I were a bird, A fair Trikeriotissa), linked according to Baud-Bovy to the ancient epitritos, is found in popular airs of antiquity, in Aristophanes' comedies, and also in Pindar.

Iambic fifteen-syllable lines, also found in Aristophanes' comedies, in Menander, and popular ancient songs, was especially widespread in Byzantium (where it acquired the name politikos, that is, popular) and ended up as the most representative metrical form in modern Greek demotic poetry (I wish for all the months in turn, Forgetful, I am truly glad, Yorgalakis, A maid was singing longingly, I would I were a bird, You quench your thirst... o sea, A fair Trikeriotissa). Of the remaining metrical forms, there is only one song with trochaic twelve-syllable lines (White doves o mine, white ring-doves), and one with iambic eight-syllable lines (A cretan ship), and one fragment, the refrain in You quench your thirst... o sea, with a trochaic eight-syllable line.

Apart from the three songs in 7/8 time, another four are of a free rhythmic type of a particularly melismatic, or decorative, character which confirms their close relationship with Byzantine ecclesiastical music. Most of the remainder are sung in duple or quadruple time, while similarly interesting instances are provided by the 12/8 time of the slow zonaradiko from Northern Thrace (You drive me mother out of home), the reversed 7/8 time (2+2+3) of the Pontic katsangell’ (A cretan ship) and the development of the syrmaticós air from Karpathos (Syrmatiko) from 6/8 time to 2/4 and 4/4 (as, conversely, the dance performed in Karpathos moves from a kato chows ('close to the ground') to gonatistos (‘with bended knees') to end as a pano choros (with low springs.)

Of special interest, too, is the occurrence of the ‘three half-line strophe' in certain songs (I wish for all the months in turn, You scold me, mother out of home, You drive me mother out of home, A maid was singing longingly, I would I were a bird, There were three monks, Syrmatiko) in which a melodic phrase covers not one but one and a half lines, a characteristic which stresses the antiquity of these songs in comparison with others in which the dominant feature is the rima (rhyming couplets, usually improvised, as are mantinadhes:When you go off to foreign lands, You quench your thirst... o sea).

Rhyming verse reached Greece with the Crusaders in the 13th century and made its first appearance in ingenious late 14th century Cretan poetry, gradually spreading to all of insular Greece since it is a verse from which lends itself particularly to poetic and musical improvisation. It is noteworthy, however, that this foreign borrowing was linked to the essential Greek verse form, the iambic fifteen-syllable line, which was taken over in turn by the French conquerors of the Aegean islands and of Cyprus, who introduced it into the popular songs of their home country. Thenceforth mantinadhes occupy a central position in Aegean tradition, displaying a diversity of themes reflecting the circumstances of the time. Indeed in some islands such as Crete and the Dodecanese the habit of improvisation is so general that the inhabitants often employ rhyming couplets when conversing among themselves, exchanging correspondence, or writing in the local press; in them, of course, couplets about their fellow islanders living abroad have a special place (When you go off to foreign lands, You quench your thirst... o sea).

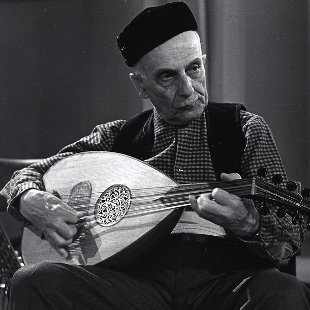

As regards the musical instruments that accompany the songs, one notes the kompania, the typical musical ensemble on the mainland of Greece, which comprices the klarino, violi, and lagouto (clarinet, violin and lute), and sometimes the santouri (dulcimer) and a percussion instrument, either a toumbeleki or deli (pottery or frame drum): Your kerchief, Yanni, White doves o mine, white ring-doves, My love-bird far away from home, A fair Trikeriotissa.

The kompania's chief melodic instrument, the clarinet, found its way into Greek music as late as the mid 19th century (it is a western instrument, though it was brought to Greece by gypsy musicians from Turkey where it had been introduced in an attempt to Europeanize Turkish military bands). By adopting the technique of the phloyera (flute) (Yorgalakis) they managed so to adapt it to the style and manner of local music that it soon acquired the character of a national musical instrument, a symbol of demotic music (see Mazarakis, D., To Κλαρίνο στην Ελλάδα , Athens , Kedros 1984, 2nd ed.).

What is particularly interesting is the way in which gypsies, most of whom are clarinet players, ornament the melody (Your kerchief, Yanni, My love-bird far away from home) by a technique which not infrequently leads to an alteration of the original melodic line of the song.

The violi is the chief melodic instrument in insular Greece. Together with the lagouto it makes up the traditional zygia, or ‘pair', (There were three monks) to which other instruments such as the santouri, kanonaki,(zither), outi (oud), and toumbeleki may be added (I wish for all the months in turn, When you go off to foreign lands, You quench your thirst... o sea).

The particular construction of the kanonaki - the trigono or epigono of the ancient Greeks, the psaltirio (psaltery) of the Byzantines - permits it to render all the intervals of the modal scales (A maid was singing longingly: taximi, an improvization by Anies Agopian in the huseyni scale). It is one of the instruments once played by Greeks living in Asia Minor which, together with the outi (I wish for all the months in turn, When you go off to foreign lands, A maid was singing longingly) has been heard less and less frequently since the Greeks were uprooted from Asia Minor in 1922. The outi is now confined largely to Thrace (You drive me mother out of home), where one finds also the gavali, a long flute with a deep tone (You drive me mother out of home). The santouri, also introduced to mainland Greece by refugees from Asia Minor, is preserved not only in the mainland kompania, but also in the Dodecanese and the island of the eastern Aegean. However, this is not so with tamboura, a long-necked lute (Yorgalakis, My love-bird far away from home), one of the most antique of Greek musical instruments (the trichordo or pandourida of the ancients, the thamboura of the Byzantines, and the instrument played by warriors in the 1821 war independence) which has for some time been under threat of extinction, particularly since the second world war.

Finally, two types of lyra (a bowed string instrument) are a case by themselves: the ‘flask-shaped' kementzes played by Greek refugees from Pontos and the ‘pear-shaped' lyre once played throughout Greece, nowadays restricted to Crete and the Dodecanese. The characteristic dissonances heard in the playing of the Pontic lyre are due to the particular technique and to its tuning in perfect fourths, while the short curved bow favours the abrupt, nervy strokes demanded by Pontic dances (A cretan ship). The same applies to the bow of the traditional pear-shaped lyre which had, and in some cases retains, another unique feature: a row of small spherical bells known in Crete as yerakokoudhouna, ‘falcon bells', because in Byzantine times such bells were attached to that bird of prey, while in Dodecanese they often refer to them as asimokoudhouna, ‘silver bells'. With appropriate and skilful movements of the bow, they underscore the rhythm and accompany the melody with the characteristic drone produced by their timbre. It is a technique rarely encountered nowadays and also fast disappearing; it was once employed by troubadours in the middle ages on an instrument similar to the lyra, the rebec or viela, and is still extant in India, being played on the sarangi, as well as in the Dodecanese.

Finally, in completing this musical commentary on the songs in the collection, one should pause a while at the Epirot song Forgetful, I am truly glad, a representative example of some unique polyphonic songs found in Greece. It is one of the most striking musical forms in the world repertoire of popular polyphonic songs. These particular songs are located in the region of the present Greco-Albanian frontier (Pogoni. Deropolis, etc.) where till 1944 Greek and Albanian communities lived together. They are performed by four to ten singers, unaccompanied on musical instruments, with a strict hierarchy respecting the role and technique of each voice. The koryphaios (coryphaeus or lead singer), called the partis-sikotis, opens the song. The second singer, the yuristis, responds, while isokrates (drones) ‘sustain the pedal'. To this group may be added a klostis who contributes falsetto vocalization weaving in and out of the song between the tonic and subtonic of the melody, Both the yuristis and the klostis abruptly cease the song on the subtonic, thus creating with the partis a sharp dissonance (with an interval of a second) which imparts a unique sound to this polyphony. Though research work has not led to any certain conclusion, there is much evidence to convince one of the antiquity of these songs that retain the pentatonic anhemitonic scale. In addition, the influence of Byzantine ecclesiastical music has affected the melodic line of the yuristis and the isokrates.

NOTE: The selection elaboration, and order of the songs has generally followed the method established by Guy Saunier, author of the fullest literary study made to date of songs of exile (see Bibliography). The criterion has been the main stages in the development of migration, or rather of the image migration conjures up in the mind of the popular poet: the migrant' s departure, his life in an alien country, the life of his family back home, his death in a foreign land, and his homecoming.

1Vilayets: provinces of the Ottoman Empire

2The City: Constantinople

Lambros Liavas, Ethnomusicologist (1989)

Translated by John Leatham

Select of bibliography

Βακαλόπουλος, Α., Άρθρα για τις μεταναστεύσεις και τους Έλληνες της διασποράς στην Ιστορία του Ελληνικού Έθνους, τ. Γ, Αθήνα 1974, σ. 66-77 και τ. ΙΑ', Αθήνα 1975, σ. 231-243.

Baud-Bovy, S., Δοκίμιο για το ελληνικό δημοτικό τραγούδι, Ναύπλιο, Πελοποννησιακό Λαογραφικό Ίδρυμα, 1984.

Βoardman, J., Τhe Greek overseas. Their Early Colonies and trade, London, Thames and Hudson, 1980

Ζώρας, Γ., Η ξενιτεία εν τη ελληνική ποιήσει, Αθήνα, 1953.

Ζώτος, Α., Η ξενιτιά των Ηπειρωτών, Αθήνα 1936.

Μαμμόπουλος, Α., Η ξενιτιά και το δημοτικό τραγούδι, Αθήνα 1970.

Μαρωνίτης, Δ.,'Αναζήτηση και νόστος τον Οδυσσέα' Ελληνικά τ. 21, Θεσ/νίκη 1968, σ. 291-346 και τ. 9-10, Αθήνα, 1955-57, σ. 105-133.

Saunier, Guy, Της ξενιτιάς, Αθήνα, Ερμής 1983.

Σβορώνος, Ν., 'Μετανάστευση’ στην Επισκόπηση της νεοελληνικής ιστορίας, Αθήνα, Θεμέλιο, 1976, σελ. 255-259.

Τερζοπούλου, Μ. και Ψυχογιού, Ελ., ‘Από τα τραγούδια στις κοινωνικές δομές'. (Βιβλιοκρισία στο βιβλίο του Guy Saunier ‘Της ξενιτιάς'), Διαβάζω 108 (1984), σ. 119-124.

Χατζηγεωργίου, Θ., Η αποδημία των Ηπειρωτών, Αθήνα, 1958.

Credits

Production team

- Domna Samiou (Research, Collection, Musical supervision),

- Lambros Liavas (Research, Collection, Musical supervision)

Sound team

- Kostas Prikopoulos (Sound engineer)

Booklet team

- Lambros Liavas (Texts and commentaries),

- Kevin Andrews (English translation),

- John Leatham (English translation),

- Pelagia Giakoumaki (Design and layout)

Singer

- Domna Samiou (Yorgalakis, You Quench Your Thirst... O Sea, I Would I Were a Bird, When You Go off to Foreign Lands, A Fair Trikeriotissa, White Doves O Mine, White Ring-Doves, A Maid Was Singing Longingly, I Wish for All the Months in Turn, The Wretched Mother Kneaded Dough, All Turn Their Gaze upon the Sun),

- Yiorgos Amarantidis (A Cretan Ship),

- Vangelis Dimoudis (You Drive Me Mother out from Home),

- Stavros Gryllakis (You Scold Me, Mother, Overmuch),

- Chrysostomos Mitropanos (When You Go off Abroad, My Love),

- Manolis Philippakis (Syrmatiko),

- Savvas Siatras (Your Kerchief, Yanni, My Love-Bird Far Away from Home),

- Christos Sikkis (There Were Three Monks)

Choir

Clarinet

- Petros Athanasopoulos-Kalyvas (A Fair Trikeriotissa, The Wretched Mother Kneaded Dough, All Turn Their Gaze upon the Sun),

- Stavros Kapsalis (Your Kerchief, Yanni, My Love-Bird Far Away from Home),

- Kyriakos Kostoulas (White Doves O Mine, White Ring-Doves, When You Go off Abroad, My Love)

Flute

Kaval

Violin

- Achilleas Chalkias (Your Kerchief, Yanni, My Love-Bird Far Away from Home),

- Nikos Oikonomidis (You Quench Your Thirst... O Sea, When You Go off to Foreign Lands, A Maid Was Singing Longingly, There Were Three Monks, I Wish for All the Months in Turn, All Turn Their Gaze upon the Sun),

- Ilias Soukas (Yorgalakis, A Fair Trikeriotissa, White Doves O Mine, White Ring-Doves, The Wretched Mother Kneaded Dough, When You Go off Abroad, My Love)

Constantinopolitan lyra

Pontic lyra

Dodecanesian lyra

Kanun

Tambouras

Santur

- Tassos Diakogiorgis (You Quench Your Thirst... O Sea, When You Go off to Foreign Lands),

- Nikos Karatassos (A Fair Trikeriotissa, All Turn Their Gaze upon the Sun)

Oud

- Antonis Apergis (You Drive Me Mother out from Home, When You Go off to Foreign Lands, A Maid Was Singing Longingly, I Wish for All the Months in Turn)

Lute

- Kostas Philippidis (Yorgalakis, You Quench Your Thirst... O Sea, When You Go off to Foreign Lands, A Fair Trikeriotissa, White Doves O Mine, White Ring-Doves, Syrmatiko, There Were Three Monks, The Wretched Mother Kneaded Dough, All Turn Their Gaze upon the Sun, When You Go off Abroad, My Love),

- Christodoulos Zoumpas (Your Kerchief, Yanni, My Love-Bird Far Away from Home)

Daouli (davul)

Goblet drum

- Yiorgos Gevgelis (Yorgalakis, You Quench Your Thirst... O Sea, You Drive Me Mother out from Home, When You Go off to Foreign Lands, A Fair Trikeriotissa, White Doves O Mine, White Ring-Doves, I Wish for All the Months in Turn, The Wretched Mother Kneaded Dough, All Turn Their Gaze upon the Sun)

Tambourine

- Yiorgos Gevgelis (When You Go off Abroad, My Love),

- Nikos Kontos (Your Kerchief, Yanni, My Love-Bird Far Away from Home)

Informant (source of the song)

- Aglaia Choutzoumi (Yorgalakis),

- Traiani and Theodor Pitsanis (You Drive Me Mother out from Home)

Member Comments

Post a comment

See also

Song

A Cretan Ship

Song

A Maid Bidding Farewell

Song

Dawn Glowed in the East

Song

Exile Is the Greatest Hardship

Song

Forgetful, I Am Truly Glad

Song

I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height

Song

My Love-Bird Far Away from Home

Song

The Ship Is My House

Song

Turtledove

Song

Well Met

Song

When You Go off to Foreign Lands

Song

You Drive Me Mother out from Home