You are at: Home page Her Work Discography Songs of Dame Sea

Contents

The wealth of Greek traditional music has been enriched by every aspect of maritime tradition – by its values, virtues and charm – as is amply demonstrated by this wonderful collection of songs. They embrace the ways people have sung, since Ulysses, about the temptations of the sea, its risks, its beauty and its tranquility but also about the danger of loss.

(barcode: 5204910000722)

CD 1

-

1. Should You See a Vessel Pass

Central Greece More

-

2. The Words Gone Round

Macedonia More

-

3. Couplets About the Sea

Dodecanese More

-

4. The Son of the Armenian

Thrace More

-

5. Koursariko

Eastern Aegean More

-

6. Three Cretan Monks

Central Greece More

-

7. A Sailor-Lads A-Dying

Dodecanese More

-

8. Kavodorítikos

Central Greece More

-

9. Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired

Eastern Aegean More

-

10. Kaklamaniko

Thessaly More

-

11. Down on the Sandy Beach

Thessaly More

-

12. Three Slender Girls

Peloponnese More

-

13. I Want to Climb up to the Top

Eastern Aegean More

-

14. Oh Yes, Indeed Did Boreas

Dodecanese More

-

15. We Kissed Each Other in the Night

Sporades More

CD 2

-

1. Little Ship, Where Are You Going

Eastern Aegean More

-

2. Exile Is the Greatest Hardship

Dodecanese More

-

3. Three monks from Crete

Eastern Aegean More

-

4. Thirty Ships Prepared for Sea

Peloponnese More

-

5. O Bitter Orange in Full Leaf

Peloponnese More

-

6. I Want to Savour All the Months

Propontis More

-

7. I Went Aboard a Boat

Eastern Thrace & Roumelia More

-

8. Lullaby

Asia Minor More

-

9. I Want to Sail Away

Eastern Aegean More

-

10. Shes a Girl From Amorgos

Dodecanese More

-

11. Our Fishing-Boat a Battered Hulk

Thessaly More

-

12. Yio Mario

Asia Minor More

-

13. Kalafatiko

Central Greece More

-

14. Somewhere in the Aegean Sea

Pontus More

-

15. At the Casement of the House

Eastern Thrace & Roumelia More

-

16. I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height

Macedonia More

- Production: Domna Samiou Greek Folk Music Association

- Year of release: 2002

- Type: CD

- Sponsors: Yannis C. Lyras

Notes

Greece is surrounded by the sea and for centuries on end the sea has determined its fate: the manner and place of wrestling a livelihood, as a gateway to communication and defensive wall, as the roadway which both unites and separates… The wild, foam-capped sea, the tranquility of a dead calm, the lapping of waves at the water’s edge: these are the image and, once many are gathered together, they turn into a song.

Immense is the sea and immense the number of songs that speak of it and with it: songs composed by sea folk on every Greek shore, whether island or mainland, each leavened with the character of the place – some light and joyful, others harsh, heavy and burdensome, yet others full of murmur and entreaty, and others still full of memories related without reference to time. From the Pontos southwards to Karpathos, from Ιerissos to Nisyros, from Kymi to Çeşme opposite on the Asia Minor coast, from the Peloponnese to Lesvos, songs of the sea travel from mouth to mouth.

I selected twenty-eight of these songs and together with three sea melodies recorded them on this collection, rendered with great love and skill, my own and that of all the others. We strove to bring them to life again. And we offer them to all who have ears to hear them, to enjoy them and to bequeath them to their children.

Domna Samiou (2002)

It should therefore come as no surprise that the Greek maritime tradition has a very long history and continues to thrive, reaching the summit of its international achievements in our times.

The wealth of our traditional music has also been enriched by every aspect of our maritime tradition, its values, virtues and charm, as is amply demonstrated by this wonderful collection of songs selected and uniquely interpreted by Domna Samiou, tireless champion of Greek traditional music, with the inspired support of her able colleagues.

In an age that is, voluntarily or involuntarily, cultivating collective amnesia these songs cannot fail to remind us how far removed we have become from our origins and our objectives. This situation represents a major loss with unforeseeable consequences.

This musical record is therefore an exercise in memory; an attempt to delve into the now shadowy depths of the ‘marine’ side of our psyche with the hope that those elements that were once such a vital part of its character will re-emerge.

We say we know ‘by heart’ the things we have learned and which are imprinted indelibly on our memory – perhaps because without feeling, thought is lost. So, in closing I would like to make this rather bold wish: ‘may the coming generation of Greeks know these songs by heart’.

Yannis C. Lyras (January 2002)

In few regions of the planet is this geological rise and fall, the close interrelationship of the two elements, so marked, both literally and metaphorically, as in that part of the East Mediterranean which includes the Greek peninsula and its archipelagos. You can survey the sea from almost every point on the mainland, while there is scarcely any point out at sea from which you cannot obtain a view of some shoreline or other. ‘Sea of the olive tree and vineyards’, that is how Braudel describes it.

Civilizations that developed along its coasts and in the hinterland of this vast caldera have never ceased their dialogue with the bewitching world of the sea, a dialogue sustained not only through maritime experience but also, and mainly, through imaginative representations of the sea itself and what it means to those whose lives are closely bound up with it: exile, riches, danger, the Unknown. The innumerable symbols of the sea that illustrate this experiential but also transcendental relationship, from depictions of ships, even of prehistoric times, in writings, art and worship down to the Gorgona in contemporary neo-Greek mythology, from chapels of Saint Nikolas to the allegorical words of demotic songs, become abbreviations with a profusion of meanings.

The life and history of this friendly sea is indissolubly bound up with that of the rugged mainland. Sea lanes are a continuation of roads on dry land and create a complex system of routes facilitating travel, transportation and communication, a network of thoroughfares along which material and cultural exchanges are effected, the inner world comes into contact with the outer, the old with the new, the traditional with change and progress. It is progress in the sense of economic and technological development – fundamental prerequisites for a seafarer to succeed and for the conquest of the sea.

Even so, in this extended continuum the sea gives rise to sharply contrasting situations. It is not so much the contrasts between the mountain-dwelling livestock farmers or downtrodden wage-earners of the countryside and restless, ingenious seafolk, between the town and the country, between civilization and cultures as the ideological and imaginary situations that emanate from a series of paradoxes of another sort. In this case the contrasting pairs are the here and the far away, security and the unverifiable unknown, Ithaca and the Sirens. Essentially, it is a matter of the deterministic chasm between those who leave and those who stay. And while seamen sail the sea, those who stay behind sing songs about it.

Demotic, or popular, songs that give poetic expression to popular thought and mythology express with lasting ingenuity the unfathomable depths of the inner character of these conflicts.

If, therefore, in reality whatever originates in the sea brings with it strength and hope, in the popular imagination whatever has anything to do with it is seductively dangerous, the alluring ‘Evil thing’, to be equated with pain, separation, estrangement; whoever succumbs to it is setting out along a road that leads to loss or oblivion. From demotic songs to Seferis, the sea is ever the cause of the same calamities, the mirror of the enormity of the same bitterness.

The verses and every word they contain become incantations that tell of the world of the sea, of the names by which the weather, the winds, the mythical lands, women and ships are named. They seem to acquire a magical power that makes the songs amphibious and able to travel to distant places, to subdue phantoms, to release the much traveled by imbuing in them an urgent desire for a homecoming; and the verses help them not to forget why on their return they will endure the most difficult crisis and why they must remember to answer clearly and correctly the Gorgona inhabiting their home waters.

Miranda Terzopoulou (2002)

The phrase used by Emperor Nikiphoros Phokas when addressing Liudprand, bishop of Cremona, ‘We are masters of the sea, therefore we hold sway’, could not but imply the enormous significance of the sea to the existence of the Byzantine state, an empire that rested its power and its economy on maritime commerce. This concept was reflected in a popular 10th-century work on dreams which stated that a person dreaming of the sea was about to acquire imperial power. Connected with this interpretation are the words ‘thalassai’ (of the sea) describing the luxurious imperial purple textiles, colored with the dye obtained from the murex sea-shell, and ‘Okeanos’ (Ocean), the name of the renowned banqueting hall in the palace of Constantine Porphyrogenitus (10th century).

But the significance of the sea was not confined to its association with authority. According to written sources, ‘thalassa’ (sea) was an appellation of the Panaghia (the All Holy, that is, the Virgin), the infinitude of God’s Mercy, the multitude of the people of the Church, a subterranean crypt beneath the chancel in early Christian churches where the water used in the celebration of rites flowed, the blessed living water that regenerates Man for his salvation and, most poetic of all, the inconstant and mercurial nature of human life:

Τοιαύτη ἐστίν καί ἡ τοῦ βίου φορά, μηδέποτε μένειν ἐν ταυτότητι

τά πράγματα, ἀλλά ποτέ μέν γαληνιᾶν εἰρήνῃ και εὐθηνίᾳ τροφῶν

ἀνενδεεῖ, ποτέ δέ ταράσσεσθαι ὣσπερ τήν θάλασσαν.

This liquid, briny and apparently harmless element has been lauded, but also has so alarmed some individuals that in Christian semeiotics it is identified with temptation and danger, and sometimes it loans its attributes to the outer forms in which death and human fate become perceptible. In painting, this complex, diverse and extraordinary world of the sea has been portrayed in many ways: smooth azure surfaces, pellucid waters stocked with octopuses, squid and other sea creatures including sea-horses ridden by Eros-figures holding reins, and scenes real or imaginary, but familiar to the human psyche, have been used to express the wealth of contrasted emotions generated by the sea. Perhaps the most interesting of these is the personification of the natural element by the figures of a woman –rarely that of a man– with lobster claws in her hair and in her hand an oar above a fish.

The model for these particular subjects were the sea scenes of late antiquity depicting Nereids and Tritons. That is why in early Christian times the personification was portrayed with a measure of restraint. Following the end in the 9th century of the Iconoclastic Controversy, it was often included in scenes such as those of the Second Coming (Last Judgement), the Crossing of the Red Sea and the Baptism, while in post-Byzantine times it appeared in scenes of, for instance, the Creation, the Praises and the Apocalypse.

It acquired particular importance, however, and was portrayed in numerous instances, in late Byzantine art when, in the critical final days of empire, the sea ceased to be the attractive feature it had been in antiquity and acquired ascetic characteristics, sometimes indeed approaching those in the iconography of Hades (Hell). Its particular symbol in this period was a ship held by a woman in her right hand and symbolizing the person of faith sailing towards the harbor of salvation, Paradise.

Finally, of special interest, and still current nowadays, is the marine version of the Gorgona, the woman with the tail of a fish, which first appears in post-Byzantine years, a borrowing from the West, representing the twin attributes, positive and negative, of the natural element. It is the primordial malefactor, but also the life-giving creature that hymns the Creator in the Praises, the Gorgona of popular mythology who is one and the same as the sister of Alexander the Great, the temptress who is to be identified with nostalgia.

The sea has the same features in later modern art. A source of inspiration identified with travel, with the unknown and the fear arising from it, with immortality, and with the desire for communication that unites men, it is rendered magically in the mermaids with loosed hair of Theophilos, the glassy blue surfaces of Spyros Vasiliou, and the abstract caiques of Yerasimos Steris. It is the protector of seafarers, the awesome countenance of the natural elements, the yearning of those living in exile, who have been transported to another land by the sea.

Magdalini Parcharidou-Anagnostou (2002)

Bibliography

JOHN CHRYSOSTOM, PG 64, pp. 19-22.

PHAEDON KOUKOULÈS, ‘Περί τα βυζαντινά φορέματα’, Βυζαντινών Βίος και Πολιτισμός, vol. VI, Athens 1955, pp. 267-294.

Λεξικό Βιβλικής Θεολογίας, Athens 1980.

HENRY MAGUIRE, Earth and Ocean. The terrestrial World in Early Byzantine Art, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987.

P. MIJOVIČ, ‘La personnification de la Mer dans le Jugement Dernier à Gracaniča’, Χαριστήριον εις Αναστάσιον K. Oρλάνδον, 4, Athens 1967-68, pp. 208-219, plates LXXI-LXXVI.

D. PALLAS, H 'θάλασσα' των Εκκλησιών. Συμβολή εις την ιστορίαν του χριστιανικού βωμού και την μορφολογίαν της λειτουργίας, Athens 1952.

M. VIEILLARD-TROIEKOUROFF, ‘Sirènes-poissons carolingiennes’, CA 19 (1969) pp. 61-82.

P. ZORA, ‘H γοργόνα εις την ελληνικήν λαϊκήν τέχνην’, Παρνασσός 2 (1960) pp. 331-3365.

Credits

Production team

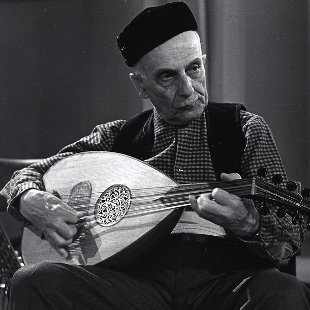

- Domna Samiou (Research, Collection, Musical supervision),

- Tasia Papanikolaou (Production assistant),

- Yiorgos Ε. Papadakis (Musical advisor),

- Socrates Sinopoulos (Musical advisor)

Sound team

- Charalambos Blazoudakis (Sound engineer),

- Christos Kosmas (Sound engineer),

- Andreas Mandopoulos (Sound engineer),

- Yannis Sygletos (Sound engineer),

- Yiorgos Ε. Papadakis (Sound editing),

- Petros Siakavellas (Sound editing),

- Yannis Sygletos (Sound editing)

Booklet team

- Yannis C. Lyras (Texts and commentaries),

- Magdalini Parcharidou-Anagnostou (Texts and commentaries),

- Miranda Terzopoulou (Texts and commentaries),

- Angela Langou (English translation),

- John Leatham (English translation),

- Yannis C. Lyras (English translation),

- Solange Matthey (French translation),

- Georgia Papageorgiou (Text Editing),

- Lika Florou (Design and layout)

Singer

- Domna Samiou (The Words Gone Round, Three Cretan Monks, I Want to Sail Away, Little Ship, Where Are You Going, Three monks from Crete, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, Couplets About the Sea, We Kissed Each Other in the Night, Should You See a Vessel Pass, Oh Yes, Indeed Did Boreas, Thirty Ships Prepared for Sea, Three Slender Girls, Lullaby),

- Kostas Antimissiaris (Shes a Girl From Amorgos),

- Vangelis Dimoudis (At the Casement of the House, The Son of the Armenian),

- Dimitris Falkis (Kaklamaniko),

- Spyros Koukos (I Went Aboard a Boat),

- Yannis C. Lyras (I Want to Sail Away),

- Dimitris Mantzouris (Yio Mario),

- Pantelis Mantzouris (Down on the Sandy Beach),

- Nikos Oikonomidis (Exile Is the Greatest Hardship),

- Yiorgos Papadopoulos (O Bitter Orange in Full Leaf),

- Katerina Papadopoulou (Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired, I Want to Savour All the Months),

- Stefania Samakoviti (I Want to Climb up to the Top),

- Nikos Yamarelos (Our Fishing-Boat a Battered Hulk),

- Ilias Yfantidis (Somewhere in the Aegean Sea),

- Michalis Zographidis (A Sailor-Lads A-Dying)

Choir

- Domna Samiou Greek Folk Music Association Choir (Down on the Sandy Beach, I Went Aboard a Boat, Three monks from Crete, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, We Kissed Each Other in the Night, Yio Mario, Three Slender Girls),

- Group of men from Trikeri (Magnesia) (Our Fishing-Boat a Battered Hulk),

- Men's Group from Karpathos (A Sailor-Lads A-Dying)

Clarinet

Flute

- Thodoris Georgopoulos (O Bitter Orange in Full Leaf, We Kissed Each Other in the Night, I Want to Climb up to the Top)

Kaval

Gaida (bagpipe)

Tsambouna

- Theologos Gryllis (Koursariko),

- Yannis Tsambanakis (Shes a Girl From Amorgos),

- Antonis Zographidis (A Sailor-Lads A-Dying)

Violin

- Nikos Oikonomidis (O Bitter Orange in Full Leaf, Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired, Little Ship, Where Are You Going, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, Couplets About the Sea, We Kissed Each Other in the Night, Should You See a Vessel Pass, Oh Yes, Indeed Did Boreas, Exile Is the Greatest Hardship, Kavodorítikos, Kalafatiko, I Want to Savour All the Months, Three Slender Girls, The Son of the Armenian)

Thracian lyra

- Spyros Koukos (I Went Aboard a Boat),

- Socrates Sinopoulos (The Son of the Armenian)

Constantinopolitan lyra

Pontic lyra

Dodecanesian lyra

- Nikos Nikolaou (Shes a Girl From Amorgos),

- Michalis Zographidis (A Sailor-Lads A-Dying)

Kanun

Bowed tambouras

Constantinopolitan lute

- Socrates Sinopoulos (Down on the Sandy Beach, The Words Gone Round, Three Cretan Monks, Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired, I Want to Sail Away, Little Ship, Where Are You Going, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, Couplets About the Sea, We Kissed Each Other in the Night, Should You See a Vessel Pass, Oh Yes, Indeed Did Boreas, Exile Is the Greatest Hardship, At the Casement of the House, Koursariko, I Want to Savour All the Months, The Son of the Armenian)

Santur

- Angelina Tkatcheva-Stathopoulou (Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired, Little Ship, Where Are You Going, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, Oh Yes, Indeed Did Boreas, Exile Is the Greatest Hardship)

Lute

- Kostas Philippidis (Down on the Sandy Beach, The Words Gone Round, O Bitter Orange in Full Leaf, Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired, I Want to Sail Away, Little Ship, Where Are You Going, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, Couplets About the Sea, We Kissed Each Other in the Night, Should You See a Vessel Pass, Oh Yes, Indeed Did Boreas, Exile Is the Greatest Hardship, Kavodorítikos, Kalafatiko, I Want to Savour All the Months, Three Slender Girls, The Son of the Armenian),

- Yiorgos Protopapas (Shes a Girl From Amorgos),

- Yiorgos Zographidis (A Sailor-Lads A-Dying)

Ney

Daouli (davul)

- Vangelis Karipis (Kaklamaniko, Somewhere in the Aegean Sea, O Bitter Orange in Full Leaf, I Went Aboard a Boat, Three Slender Girls)

Toumbi

Goblet drum

- Vangelis Karipis (Little Ship, Where Are You Going, I Wish to Climb a Mountain Height, Should You See a Vessel Pass, At the Casement of the House, Koursariko, I Want to Savour All the Months, The Son of the Armenian)

Bendir (frame drum)

- Vangelis Karipis (Three monks from Crete),

- Yiorgos Ε. Papadakis (The Words Gone Round, Three Cretan Monks, I Want to Sail Away)

Tambourine

Zil bells

Informant (source of the song)

- Assinou Bounia (Should You See a Vessel Pass),

- Yiorgos Demerdjis (At the Casement of the House),

- Dimitris Falkis (Down on the Sandy Beach, Kaklamaniko),

- Nikolas Labrinoudakis (Yio Mario),

- Paraschos Manikas (Yio Mario),

- Zacharias Mikedis (Dear Mother, I Am Awfully Tired),

- Amalia Papastefanou (Exile Is the Greatest Hardship),

- Yannis Parisis (We Kissed Each Other in the Night),

- Evangelia Sarantinoudi (Three monks from Crete),

- Yiorgos Tzitzos (The Words Gone Round),

- Dimitris Vlaskos (I Went Aboard a Boat),

- Philissia Vourtzoumi (I Want to Climb up to the Top),

- Nikos Yamarelos (Our Fishing-Boat a Battered Hulk)

Member Comments

Post a comment

See also

Song

All Attend at Church

Song

I Sold My Boat

Song

I Went Aboard a Boat

Song

Kaklamaniko

Song

Little Ship, Where Are You Going

Song

Our Fishing-Boat a Battered Hulk

Song

Ribbon Interwined

Song

Should You See a Vessel Pass

Song

The Great North Wind Blew

Song

The Sea Has Made Me Old

Song

The Ship Is My House

Song

The Words Gone Round

Song

We Kissed Each Other in the Night

Song

Yio Mario