The Known and the Unknown Domna

Information

- Period: 29/10/1998

- Location: The Athens Concert Hall, Hall of the Friends of Music

- Production: The Athens Concert Hall Organisation

Precious comfort

One does not need to be equipped with special powers of observation to detect in Domna Samiou’s face her passion, her unequivocal goals, and her deep concern for even the slightest detail associated with her work.

She grew up in the hard years that fate had in store for the uprooted people of Asia Minor. Nevertheless, as happens in every ordeal, consolation and courage gain ground and prosper in many ways in human hearts. Among their other heirlooms, the Asia Minor refugees treasured their songs, precious comfort and balm to the bitterness, troubles and trials of the soul.

During the 1930s, when as a child Domna was exposed both within her own family and in the broader social context to the influences that were to mould her character and spirit, folksong and everything connected with it were regarded with a particular seriousness, unprecedented in its history.

Discussions and argument were already rife among scholarly musicians (such as Kalomiris, Lambelet, Varvoglis and Psachos). They posed a variety of questions directly or indirectly associated with ‘national’ music and, of course, folksong. The invention of a process by which sound could be preserved on gramophone records, and the gramophone itself, presented new possibilities and radically changed the situation that had previously prevailed.

These developments and their impact began to be felt in Greece shortly before the decade of the ’30s and galvanized the whole field of demotic, or popular music. It was then that two important organizations were formed: the Popular Song Society, founded in 1930 for the purpose of recording folk music according to strict folkloric criteria, and Simon Karas’s society with similar aims, founded in 1936.

Their activities have left us a large number of invaluable recordings, and have heralded the start of a new movement that not only encouraged the identification, promotion and preservation of monuments of folk culture but also fought against the distortion that accompanies misguided commercialization. Not a few people in the coming years were recruited to this cause, which they have supported either openly or behind the scenes. One of the most active and most effective has been Domna Samiou.

Very early on, at the age of thirteen, she found herself among the students of the Society for the Dissemination of National Music, where she had the opportunity to study and learn the secrets of folksong from Simon Karas. From 1954, when she began to work at Greek Radio, she devoted herself to the enormous and difficult task that included, apart from the study of interpretation, the recording, classification and promotion of the material which she herself collected on her frequent travels to even the most distant and inaccessible parts of Greece. In 1960 her activities expanded into the field of record production.

After 1971, when she left the Radio, her efforts intensified, yielding a rich harvest of folk music material. It was in 1971 that she appeared for the first time as a performer. The public gave her a warm welcome, not merely as another good popular vocalist but also because they recognized her whole endeavor to be an act of faith, something that set her apart and won her a special place in their esteem.

Her experience and knowledge later became the foundation and starting point of a series of documentaries –Musiko Odiporiko (Musical Travelogue)– for state Television which was unique at the time.

With the passing of the years the prevailing view of folk music in the media (records, radio, TV) has been confined to a rather shallow, picturesque image that serves commercial purposes alone. The popularization process has fossilized tradition and made it not only a dead letter but even dangerous. This is because the only thing remaining to it is this picturesqueness, a quaintness that is in no position either to show us ourselves as we are or to link us truly with our roots.

The quicker the deeper meaning and value of tradition vanish behind simplistic forms and diverse acts of expediency foreign to it, the more urgent the need to reveal and illuminate tradition’s beauty, joy and usefulness to contemporary society. In this battle, and indeed in this frontline, Domna Samiou stands out. Her concerts in Greece and abroad, her research, her recordings, her publications and, above all, her passion and readiness to engage in this endeavor make her worthy of the greatest honor reserved for dedicated people.

Yiorgos E. Papadakis (1998)

Translated by John Leatham

I have a string of hearts; I’ve laid them out in the sun*

At an exhibition on India, which I happened to see a few years ago in a folk art museum in Europe, inspired museum curators and ethnologists had impressively recreated part of a small Indian village in their attempt to include all the characteristic, functional features of the local traditional culture. On the floor in a corner of the farmhouse, next to the niche containing the family’s shrine filled with images of gods, candles, flowers and fragrant incense, a battered old valve radio could be heard sputtering, as if forgotten, in the empty room. It was playing a Beatles song.

The unfamiliar sound transformed the faultlessly contrived space into a place of fantasy and truth. This fabricated jarring note, which exposed a problem with both an aesthetic side to it related to the approach to tradition freed from the constraints of stereotyped perceptions and popular taste, was what contributed most to the creation of a delightful atmosphere of discreet plausibility. By means of the music, the elements of the culture contained within that mud hut lost the exoticism that the sound of the sitar would have lent them, yet they acquired and accentuated all the power of centuries’ old progress through faith and poverty, which made the Indian peasant missing from the scene capable of fearlessly associating with the music of the boys from Liverpool.

Impressed by that museum-generated find –so innovative for those times– I remember thinking that perhaps the unexpected, the non-self-evident, the unforeseen, when endowed with an aesthetic quality and a timely symbolism, make the essence of the thing focused upon more evident, revealing more obviously what it so resolutely possesses.

That memory has become enmeshed with one of the sharpest, most intense images I have of Domna: in Monemvasia under the full moon, she is singing the songs of Sophia Vembo for a group of friends in a high spirited, relaxed manner, but one imbued with inscrutable emotions. From the overtones of that musical treat I understood then that when her great skill plays on the unknown fringes of her mood it defines more clearly the momentous nature of the task with which we have all identified her, and which she serves with such unswerving devotion that we take it for granted and often lose sight of its importance. (Indeed, why should it be taken for granted that such a voice has consecrated itself for life to the thankless field of folksong?)

When I hear Domna sing any other kind of song with that voice, giving it, even momentarily, her particular stamp, I understand the burden and significance of her choice and moreover of her sacrifice.

What is even more impressive, mainly for those who know her and work with her, is that Domna herself does not seem to be aware of the importance of what she represents and of the task she has undertaken. The constant feeling of an unpaid debt, her agonies about fleeting time, which make her feel that she has not done or will not manage to do as much as she should, make us suspect something. Everything suggests that her personal history, her background, the uprooted refugee circumstances of her youth with its hard life and mute pain have produced the quenchless thirst, the flame, the tireless energy, the constant searching that characterize her – as if they were the only form of protest and the only possible resistance to the threat of deterioration and oblivion, the only feasible way of reversing disaster.

With her unvarnished natural presence and her resonant voice revealing the secret essence of the songs, she pays tribute to all those who heard them and sang them before they came down to her. After all, she first learned to sing and mainly to listen in the especially sensitive refugee surroundings in which she grew up, following the time-honoured oral tradition.

Ever faithful to this relationship of honour and debt, she unfailingly proclaims, with knowledge and conviction, her respect for what belongs to the past and her absorption and trust in the authenticity of all those anonymous interpretations by her anonymous teachers who forget both her art and her spirit.

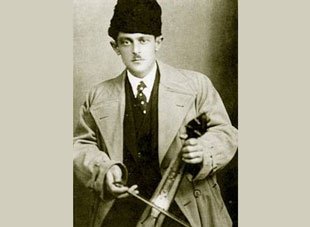

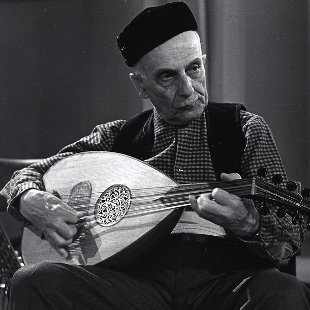

Simon Karas, treading the similarly traditional path of the strict teacher-pupil relationship, further shaped her learning, her voice and her technique; but mainly he set her on the road to research and to the prospect, with its moral and intellectual aspects, of passing on her discoveries, guiding her towards the double, or rather triple, career she later pursued.

Thus Domna became the many-sided, unique personality that she is: simultaneously the advocate and recorder of traditional music, student and interpreter of folksongs, collector and producer of records, and teacher and animating spirit both of the young as they turn to the traditional and of the older as they rediscover it.

In this respect her talent as a singer has been particularly decisive. It has led her to take a different approach to folk music, one which is both modernized and modernistic, even though she herself does not admit it. Along the way she studies and reveals its purely artistic dimension and value according to strict criteria, yet always takes into account the inclinations of her personal musical temperament.

In the unknown songs that she seeks out and discovers, it is the historic past they embody and their ritual gravity that attract her more than their intellectual dimension; the older modes, the rarer scales, the slower, more difficult melodies fascinate her, challenge her, because they give her the opportunity to promote her vocal identity, perfect her technique, show off her skill, and play with the unusual registers of her voice.

Domna however is unusual in another sense. She is one of the very few performers whose personal art is not at odds with and does not violate the strict codes of collectivity which govern traditional music. The folk origins of her persona and her genuine love of joining in wherever and whenever she can, her familiarity with almost every musical idiom, her tremendous experience and expressive capabilities, which have incorporated the riches gained from endless hours of listening to a vast range of songs, naturally lead her to place her personal stamp on everything she sings.

She is entitled to do this not only because she does it perfectly, but because this exceptional woman is and feels herself to be entrusted with a lived and living musical tradition that, like everything else alive, does not, cannot, stay the same, unaltered, but must accept new blood in order not to be lost and to be passed on to the next generation.

Domna, who knows what it means to lose an essential part of oneself, to be deprived of the past and culture of one’s land, but who was fortunate enough to be entrusted by her anonymous teachers with their precious memories, unwritten history and the secret codes of their musical language, has shown that she knows better than anyone something else: how to love, respect and safeguard the fortunes of others. Even when they themselves did not know their value, Domna took their inestimable heirlooms and with her love re-endowed them with light and life, before humbly restoring them to their rightful owners: ‘What is yours is yours’. She had but one request to make by way of recompense: that they should not let them degenerate, but treasure them and hand them down to those who come after.

From what she took and she gave, Domna has never kept anything back. For her crystalline clarity and sincerity are essential. Perhaps this is what makes her even today reveal to us her small, unknown loves, loves which, dedicated as she is so totally to the task to which she has consecrated herself, she has not had the time to enjoy and devote herself to – I am sure she would have devoted herself to them with the same passion – though they are always hovering around the edges of her horizon, beckoning to her. May they be the occasion for us to get to know something we do not know, but also once again to see something we do all know about her, our familiar but unknown Domna.

*Lines from the poem ‘Arapia’ (The Negro Race) by Matsi Hatzilazarou, included in the collection ‘Eros Melachrinos’ (Black Eros), Ikaros Publications, Athens, 1979.

Miranda Terzopoulou (1998)

Translated by John Leatham

Beautiful, brave Greek woman

I was introduced to Domna in the winter of ’64 by Alexandros Patsifas. I was under the New Wave label then, but the music that gladdened my heart was that of the great rock groups on the one hand and of our folk songs on the other.

Among my friends, Tassos Falireas personified rock. Folk songs acquired a representative as soon as I met Domna.

Under her musical supervision, some 45 rpm records had just been released with some of our folk music virtuosos and their improvisations. You listened to them and felt your life change. I practically had them under my pillow in those days.

In ’69, after the success of the song Dirlanda, the late Patsifas persuaded Domna to find him something similar for me to sing, and our friend, out of respect for Patsifas, brought me a whole lot of songs with a lively rhythm and group refrains like Dirlanda, songs from Macedonia and the islands, wonderful things, but I was not in the mood to do another Dirlanda, nor was I interested in becoming an arranger of folksongs.

What I was interested in was Domna herself.

That inveterate collector of old and rare songs had a talent for singing and playing these songs in such a way that she revealed their deeper essence and inspired artistic emotion in the listener.

She was not simply a folk historian. She was a folk historian-artist, a combination unknown in the west, and something that would have remained unknown in Greece too if Domna Samiou and two others had not happened along: Simon Karas, above all and pre-eminently, and Ross Daly.

But, of the three of them, I love Domna, because she has influenced us deeply. While she was familiar and unassuming, she was also everyday. You hardly noticed her. Not even she herself had learned her own value.

I wonder, do the younger Greek songwriters know what they owe to this woman who brought to light the old city songs of Constantinople and Crete? The wind instruments of the Macedonian towns?

What would Nikos Papazoglou or Sokratis Malamas and our other major young songwriters be if Domna Samiou had not introduced us –in the ’70s– to the song As heavy as iron is the weight of our black clothes? This unknown and strangely evocative piece was dug up by Domna to become, years later, the archetype of almost all our younger generation of music.

She was scrambling up stony hills and gathering unknown songs from grandfathers. The only thing left was to persuade her to come to the microphone and sing them herself.

I hope we didn’t do her an injustice.

When she appeared for the first time in 1971 at the Rodeo on Heyden Street, something like a tidal wave occurred. With her voice she made us understand the difference between the great tradition of her art and the cheap folklore of the colonels. The folk song returned luminous and cleansed. Like the sea. And the young were there to see it.

Wicked tongues said, ‘Domna’s finished, she descended into the dives where the long-haired boys hang out’.

But we knew that Domna was, first of all, beautiful because she had overcome her senseless misgivings, brave because she had given her all and, third, a Greek woman because that made her dispense with the false distinctions between theory and performance and she did it with the utmost naturalness – simply and directly.

May God preserve her.

Dionysis Savvopoulos (September 1998)

Translated by John Leatham

The Known and the Unknown Domna

Images

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

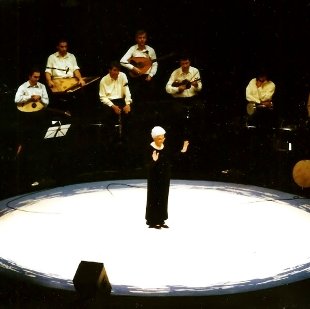

With Lykourgos Angelopoulos and the Greek Byzantine Choir

© Stefanos

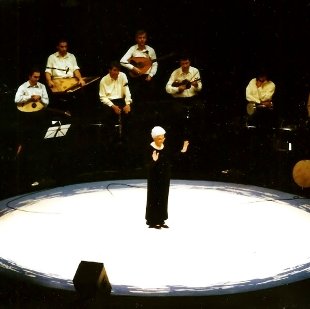

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

With the Domna Samiou Greek Folk Music Association Choir

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Domna Samiou

© Stefanos

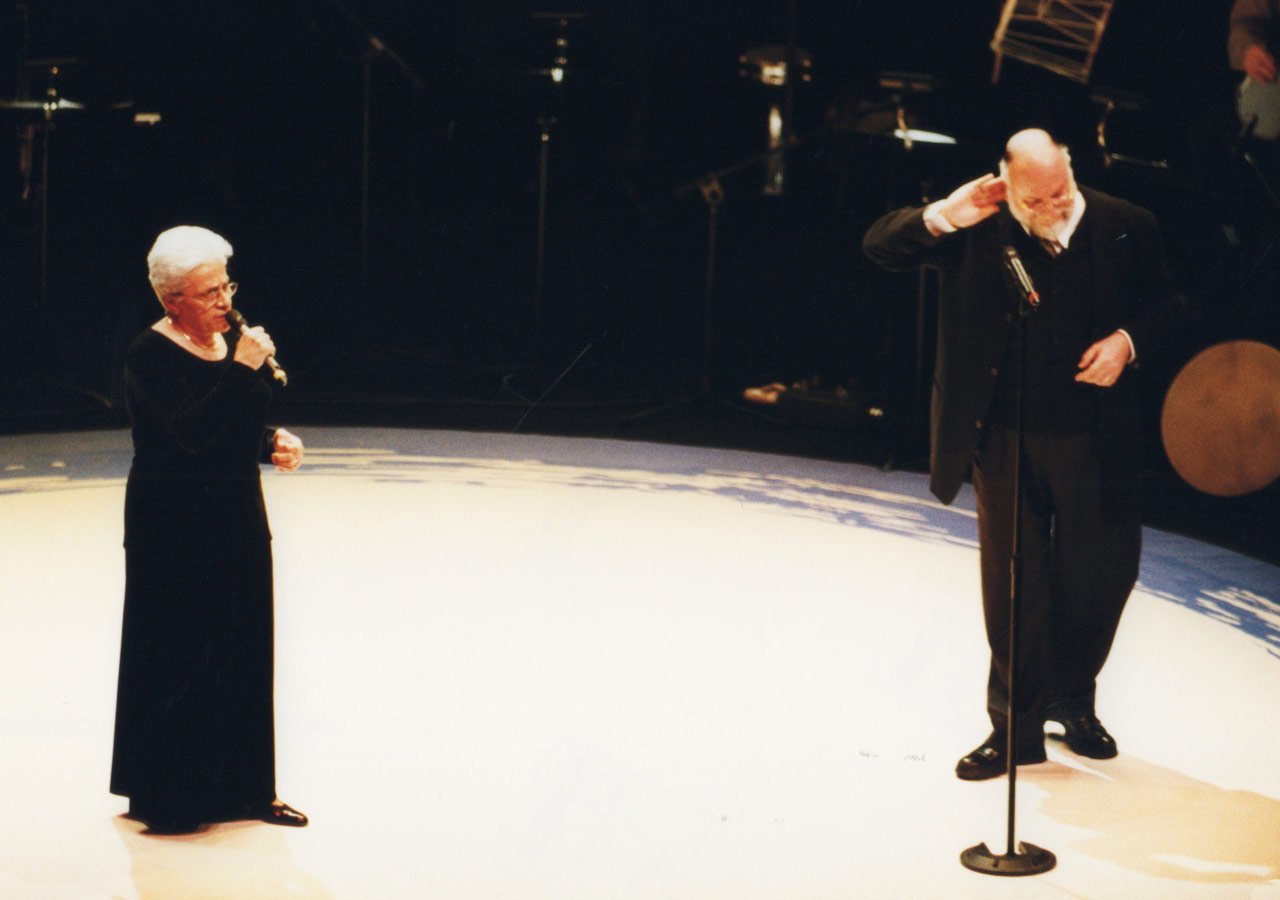

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

With Dionysis Savvopoulos

© Stefanos

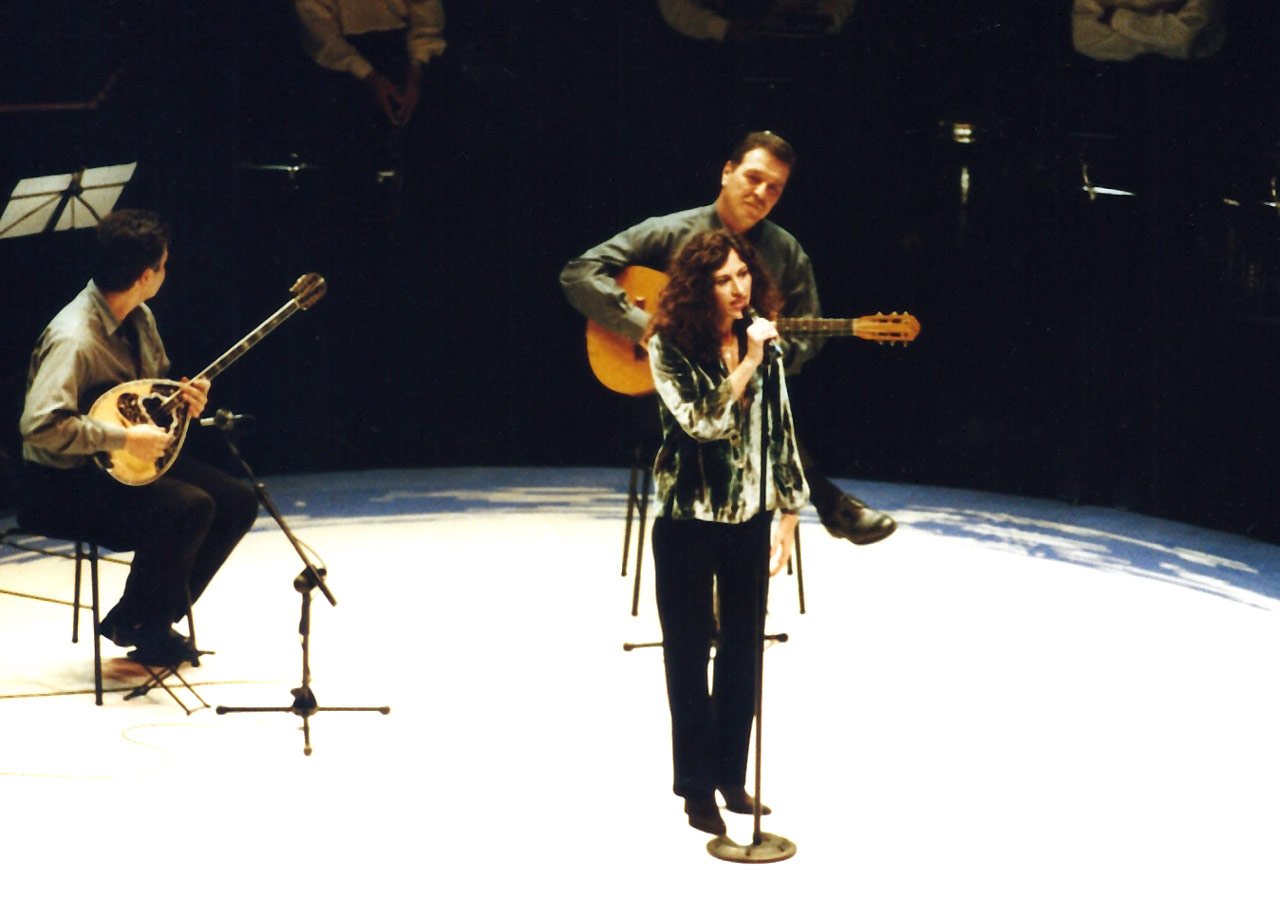

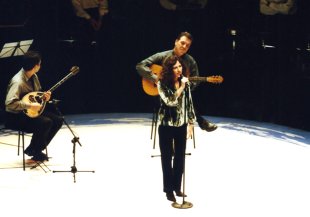

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Eleftheria Arvanitaki with Spyros Goumas and Vassilis Kasimidis

© Stefanos

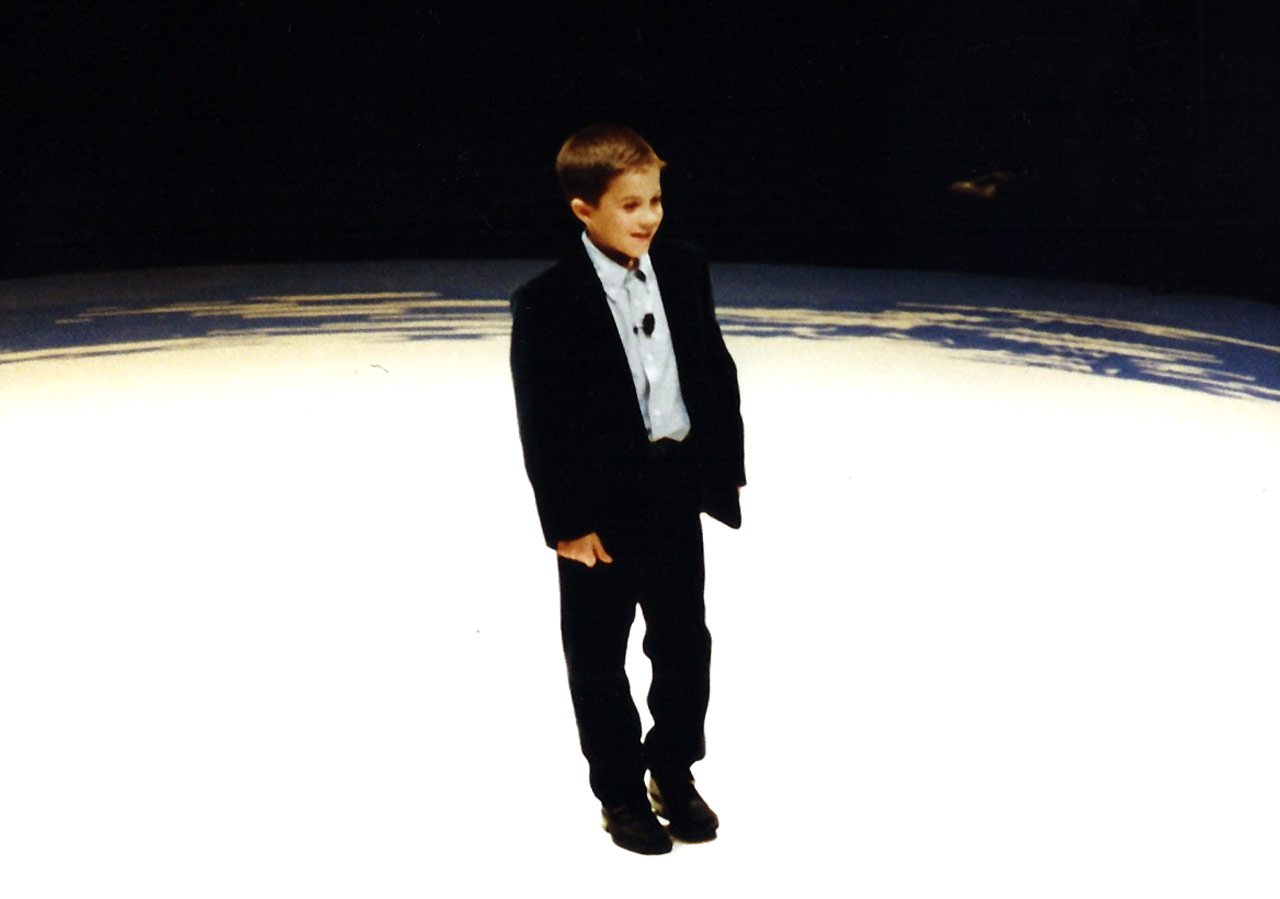

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

With Dionysis Savvopoulos and children's choir

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Yiorgos Papadopoulos

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Socrates Sinopoulos, Panos Dimitrakopoulos, Nikos Philippidis, Kostas Philippidis, Nikos Oikonomidis

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Vassilis Pierrakeas, Vangelis Zografos, Iraklis Vavatsikas, Nikos Sakellarakis

© Stefanos

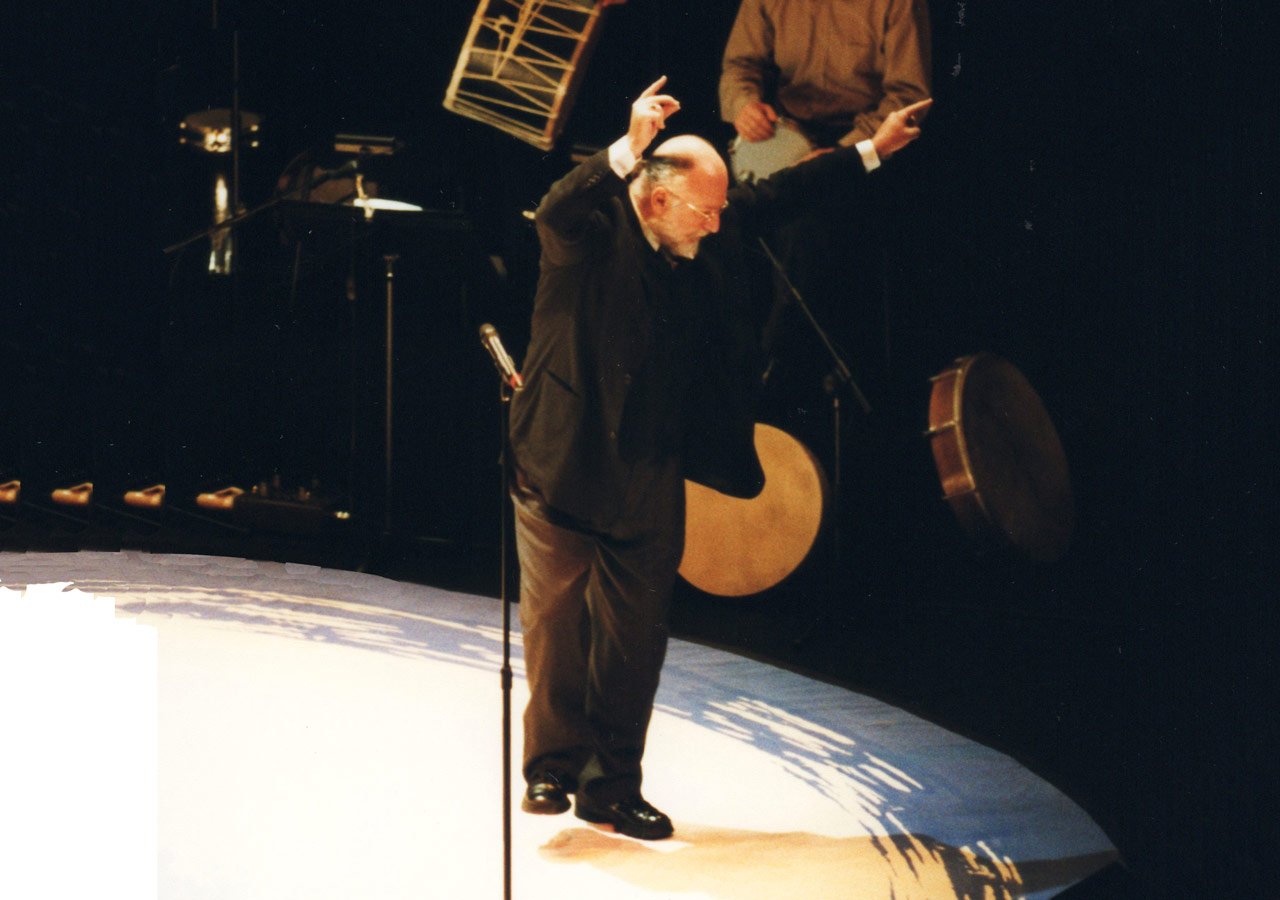

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Dionysis Savvopoulos

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

With Maria Delogianni, Thanassis Samolados and Panagiota Dagia

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Children's group from Xiropotamos, Drama

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

Closing the concert

© Stefanos

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

With Yiorgos E. Papadakis, from the rehearsals

Athens Concert Hall, 1998

With Dionysis Savvopoulos and Yiorgos E. Papadakis. From the concert rehearsals.

Collaborators

- Singer: Domna Samiou, Eleftheria Arvanitaki, Dionysis Savvopoulos

- First Chanter: Lykourgos Angelopoulos

- Choir: Domna Samiou Greek Folk Music Association Choir, The Greek Byzantine Choir

- Clarinet: Nikos Philippidis

- Flute: Nikos Philippidis

- Violin: Nikos Oikonomidis

- Constantinopolitan lyra: Socrates Sinopoulos

- Kanun: Panos Dimitrakopoulos

- Bowed tambouras: Fahrettin Çimenli

- Constantinopolitan lute: Socrates Sinopoulos

- Santur: Angelina Tkatcheva-Stathopoulou

- Lute: Kostas Philippidis

- Ney: Volkan Yilmaz

- Percussion: Yiorgos Gevgelis, Vangelis Karipis

- Supervising director: Daphne Djaferis

- Musical advisor: Yiorgos Ε. Papadakis