You are at: Home page Domna Samiou A Tale of a Life Childhood Years

Childhood Years

Text

You can imagine how much poverty there was. I remember that many times at home there was nothing to eat for dinner. We would buy a preserved herring from the grocer's and my father would light a newspaper to cook it. The four of us would share it. We would eat one herring and because it was salty, we would drink lots of water, our bellies would swell and we would go to sleep.

Clothes? I remember that we would get shoes once a year, when we could afford it.

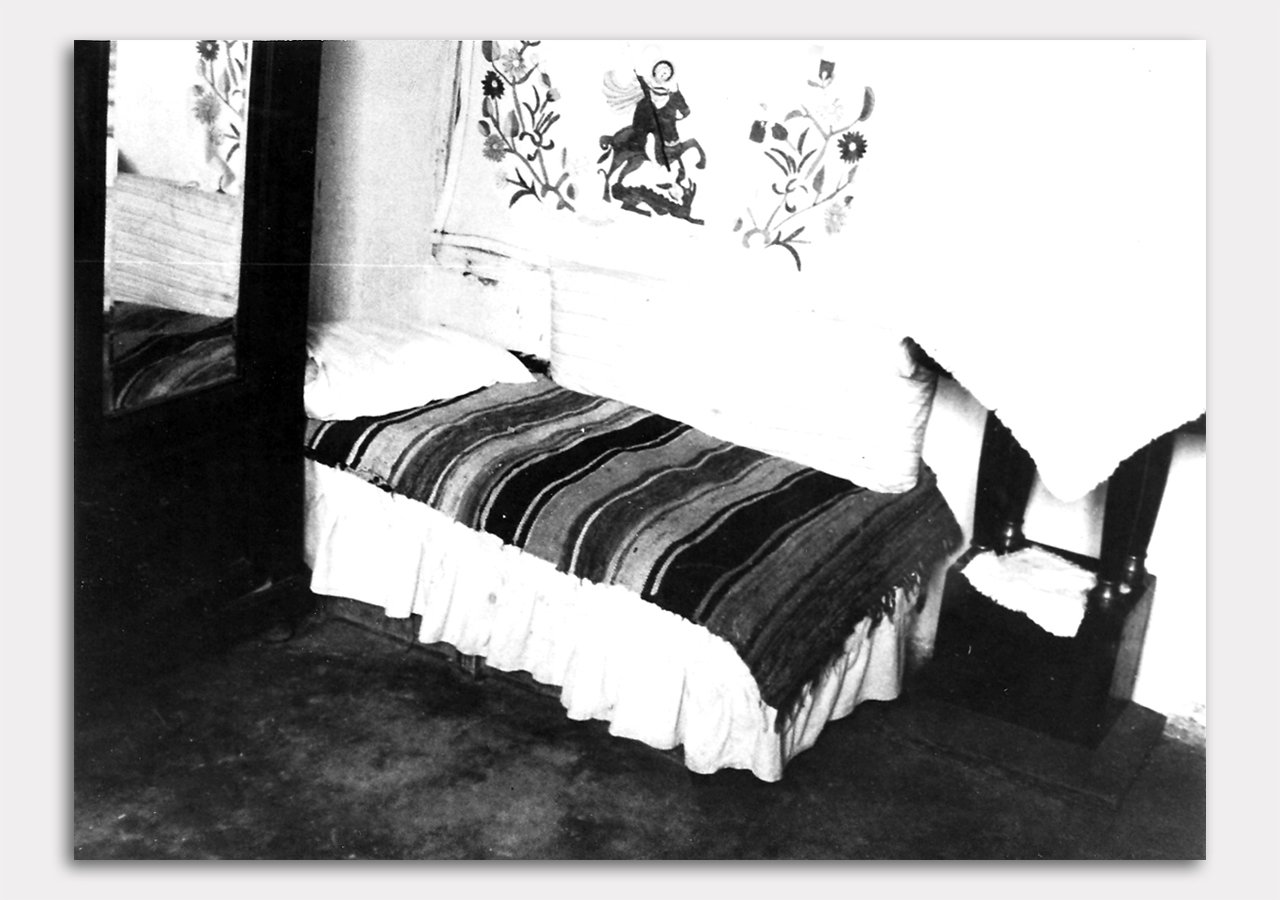

In winter our shack would leak, because we were at the lower level. Opposite us there were other shacks, not even built houses, but since those people were a bit better off, they put tiles to stop the water getting in. Whilst the rest of us were given a roll of tar paper each by the municipality every autumn. The men would lay it out on the roofs and nail it down with wooden laths, but when the wind was very strong it would tear them apart and the rain would come in. My poor mother would take all the cauldrons, pots and pans and put them wherever the water dripped. I remember that many times it even dripped on the bed my sister and I slept on. Mother would role up the mattress, preventing it from getting wet and mouldy, put it to the side and get us on top of it. We spent some nights completely sleepless on the mattress. That was a constant problem, until the shack finally burned down.

You can imagine how much damp there was in the shack. To try and heat it, my mother would buy charcoal dust from old Mr Alekos. The dregs of simple charcoal, not coke. She would also buy lime and kneed them together into small lumps like little loafs of bread. She would then put them out in the sun to dry, and once dried, would store them in cans until winter, when she would burn them in the stove. My mother also owned a brazier. It was a small metal barrel which my father had secured with bricks to use as a brazier. That is where my mother cooked and boiled water for the laundry. She would do the laundry in a trough. She also had a basket in which she would put the laundry, cover it with a special cloth on which she would place ash, and then poor water through.

For lighting we had petrol lamps. Our better one was of bronze and my mother would get me to polish it with lemon and ash. In the kitchen we had the likes of those glass round ones.

Naturally our neighbours were all from Asia Minor. Despite the sadness and pain they had over losing their possessions, their homes and their homeland, these people slowly found work here and did not lack in spirit.

They would go to the taverns that sprang up around there, drink a little wine or ouzo and sing. They were hearty people. If there was a wedding for example, they would all help out. The men would wear table cloths around their waists and help out as waiters, laying tables in the yard. Or if a woman was going to give birth, all the women of the neighbourhood would rush to help her deliver, wash her clothes, cook for her and wash her dishes. And if there was a funeral, again everyone would help. It was not like it is today, where you live in an apartment block and don't know who lives above you, bellow you or next to you. There people knew each other in the neighbourhood and would all help each other out.

There were all sorts of characters there in our community. First and foremost I remember the pesvandis. Pesvandis must be a Turkish word... So this night’s watchman used to wear khaki breeches, like the Cretans do, and tall black boots as the people from Vourla do (there was another neighbour from Vourla and he also used to wear them). He would do his rounds three times during the night, once around eleven o'clock, once around one in the morning and once around three. He would neither talk, nor shout. He would simply carry a hefty rounded wooden staff and wherever he had spotted rocks on the ground, he would knock them making a resounding sound two or three times to scare away any thieves.

This man, the pesvandis, would use his staff first of all to warn any thieves to leave because he was approaching and also, I imagine, to use as a defensive or even offensive weapon. He would make his rounds at noon on Sunday and we would give a drachma each. That was his reward.

The only 'thief' I remember was 'Psahoulas'. Because it was very hot inside the shacks during the summer, most people would sleep outside. They would lay their bedding on a small ledge outside their homes if they had one or on small cots, or on the ground. Or they would sleep with the doors and windows of their shacks wide open. So this unfortunate sod 'Psahoulas' would not steal anything. He would go wherever there was a woman or a young lady, put his hand under the sheets and grab a leg or a thigh. And people would say 'Psahoulas made his appearance again tonight'.

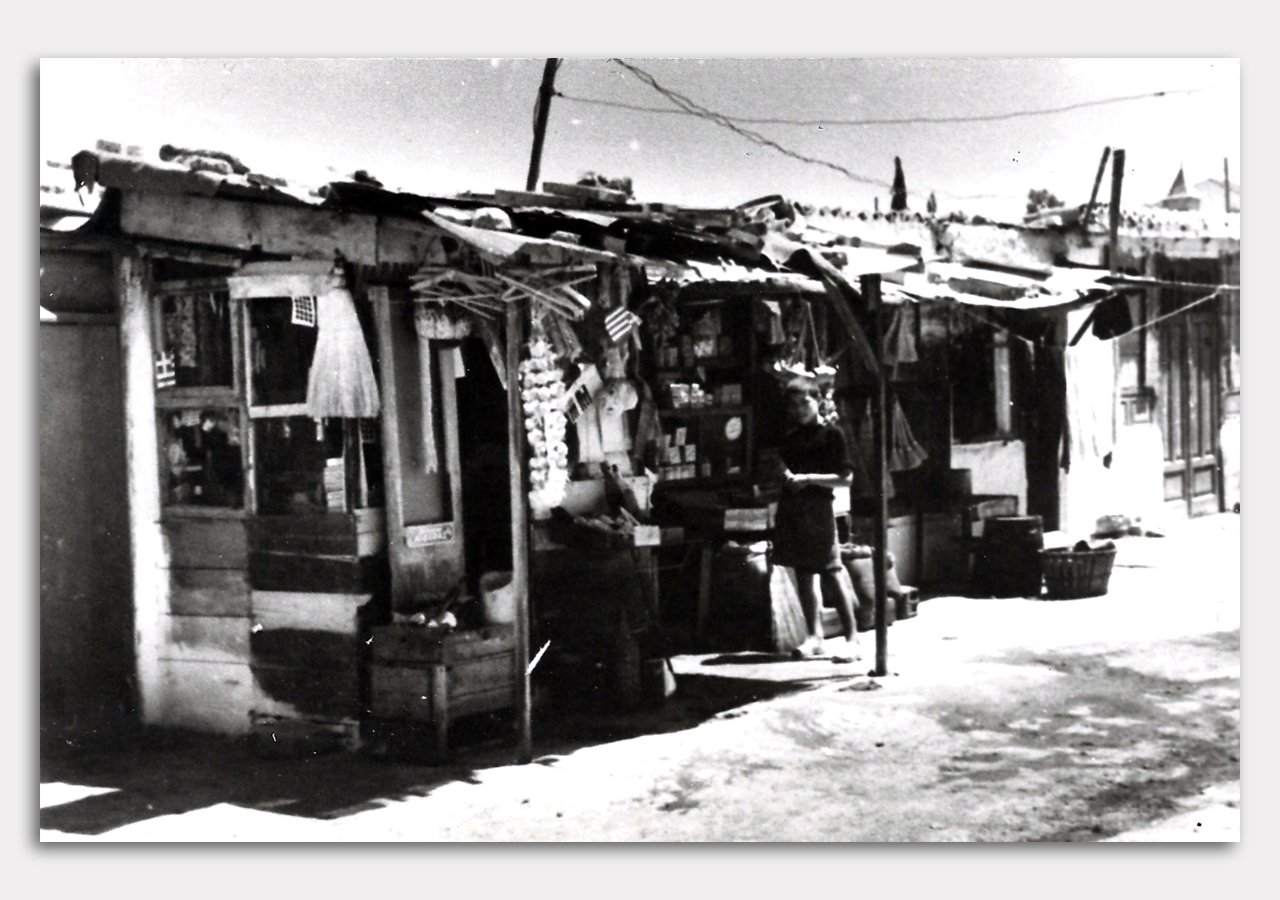

Another character was the town crier. What today has become the science of advertisement, which floods our ears from the radio and television, back then was a blind man who would walk around with his walking stick, led by a small boy. I remember him well. He would go to the corners of the blocks in the neighbourhoods and advertise, and was, I guess, paid by the person he advertised. There was a well known butcher’s store in Kaisariani, Stravaridi's butcher store, and the town crier would yell, especially on Saturdays since that is when people would go to shop.

- 'Today at Stravaridi's butcher store you will find veal for thirty drachmas and lamb for...!' or 'A small child has been lost, if anyone finds it he should bring it to the police station!'

Meat was not something that we or the others had the financial means to eat as people eat it today. We would buy meat once a week, so Sunday was a big day for us. On Sunday we would put on our best clothes, my father would shave to go to church and our whole mood would change. Whilst on week days we would eat pulses, rice with leaks, rice with spinach, herring cooked on newspaper, salad, various soups or salted cod. Those were the dishes that I remember. Of course in the summer there were egg plants, okras, all those. But not as they are cooked today all mixed together. Egg plants separately, okras separately. One dish in each pot.

As for sweets, my mother used to make fruit preserves. She didn't use to make baklava, ravani and the likes. In the summer she would take grapes and make grape sweet. Or she would take watermelon or the peel of bitter oranges, roll them up and make what she called 'karoulaki'. My mother also used to do another thing, she would take long thin egg plants, cut them down in the middle, remove the inside and thread them into bunches. She would also thread okras. Then she would hang them out to dry and keep them for winter, when she would boil them. We also made trahana and tomato paste. Women would buy tomatoes and lay them out on trays on the easily accessible roofs of the shacks. In the summer the whole neighbourhood smelled of sour tomatoes. They would also make fide. They would mix dough from flour and use the 'kalbouria' as we used to call sieves. My mother would also make tsakistes olives, with olives she would buy from the street market. There was a street market in Pangrati and the women used to go there and carry stuff back. In fact it was one of my great pleasures being taken to the street market, I really used to enjoy it. She also used to make pickled anchovies.

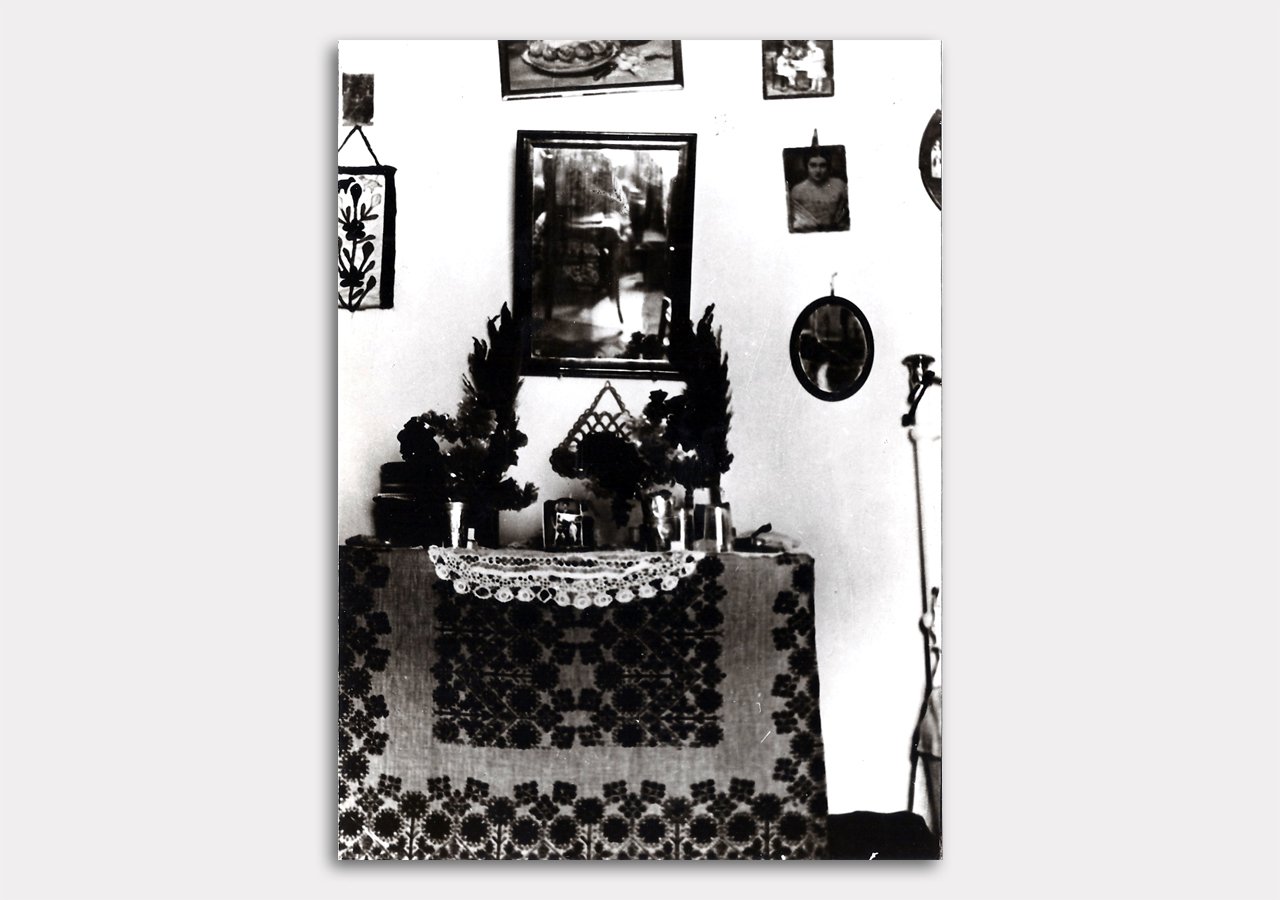

The women also used to knit of course, the so called 'pitsini'. Aunty Elenitsa would always be making little round crochet patches and then join them up. My mother had little [crochet] curtains on the windows. On the ground we had kourelou rugs.

Childhood Years

Images

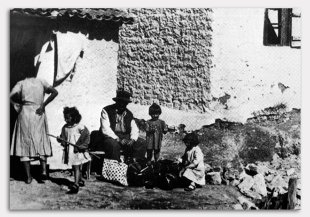

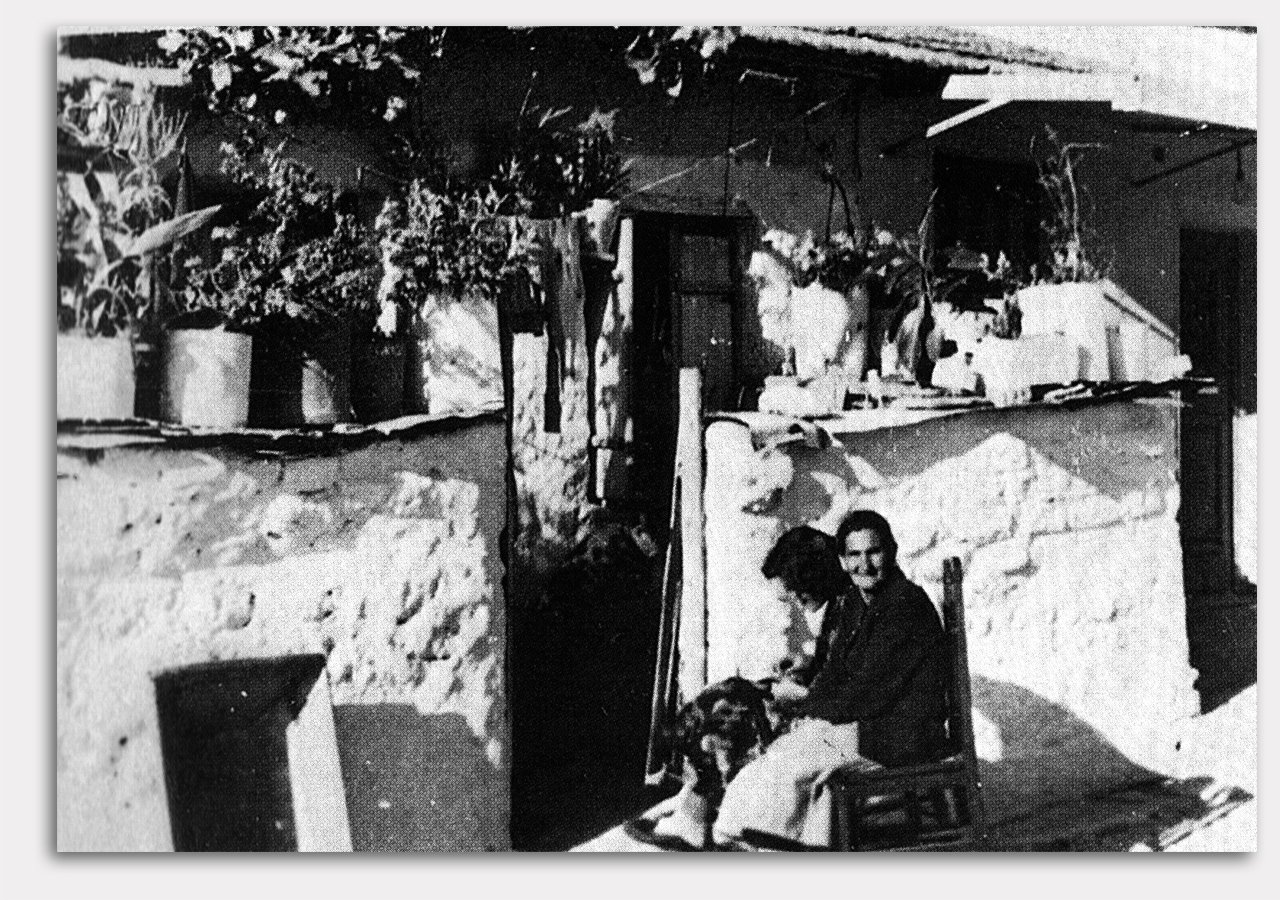

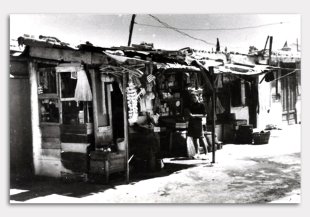

Kaisariani, 1940s

photo Elli Papadimitriou

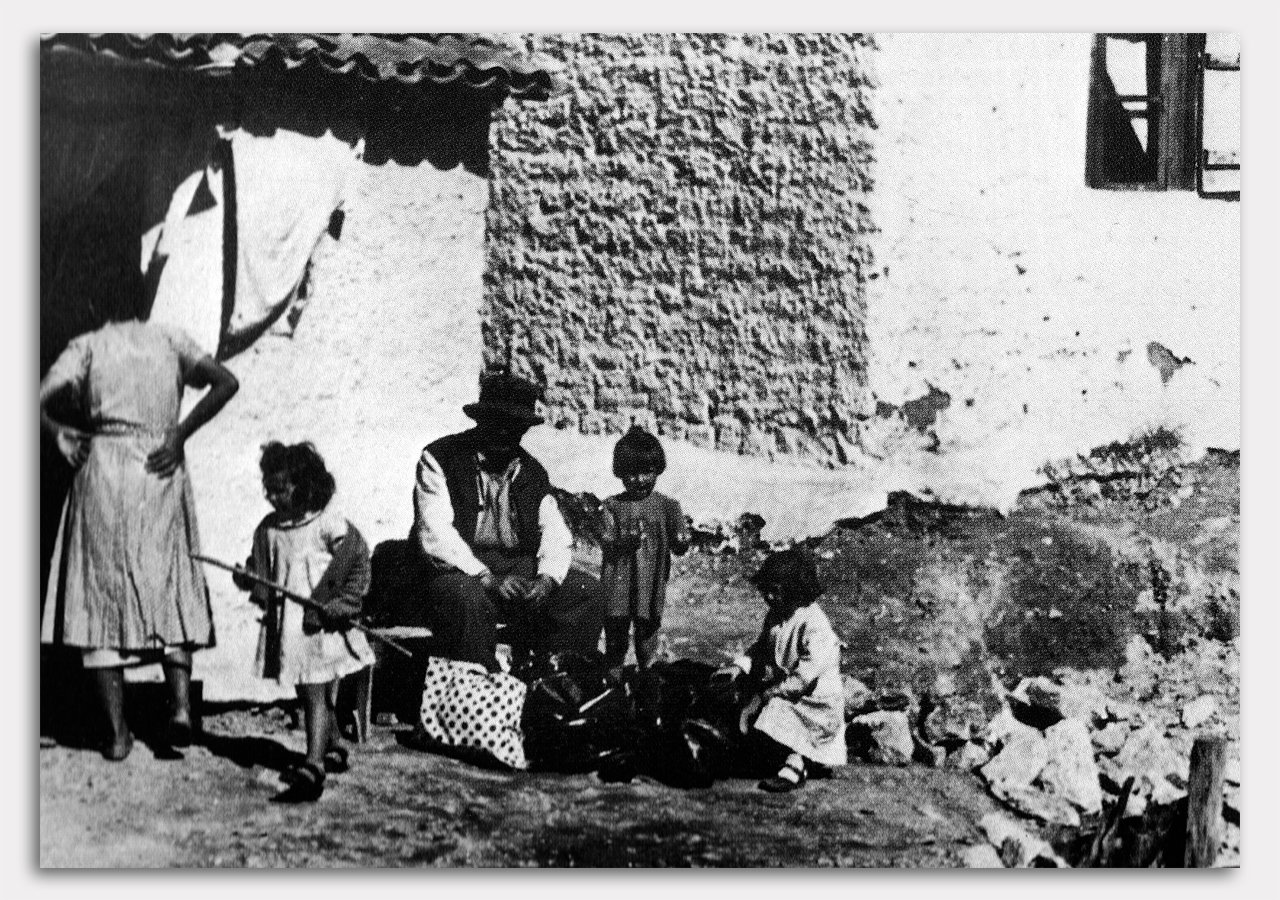

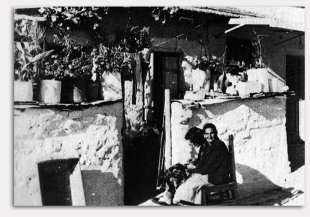

Kaisariani, 1940s

photo Elli Papadimitriou

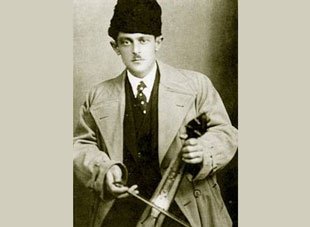

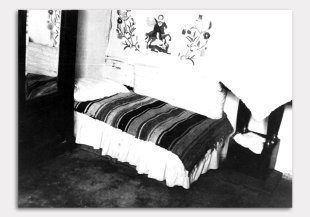

Kaisariani, 1940s

photo Elli Papadimitriou

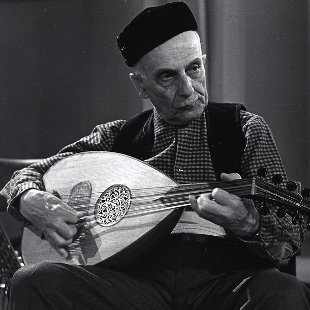

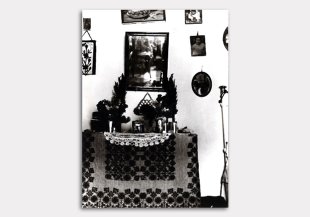

Kaisariani, 1950s

photo Elli Papadimitriou

Kaisariani, 1950s

photo Elli Papadimitriou